Samurai movies make it look like honor-bound warriors vanished in a single blaze of glory, swords drawn. But history had other plans. Behind the myths lies a gritty reality of shifting loyalties and cultural reinvention. If you think you know how the samurai era ended, think again. Let’s cut through the legend and face the truth. Ready to challenge everything you thought you knew?

Samurai Fought With Honor Until The Bitter End

Not every samurai clung to noble ideals as Japan modernized. Some abandoned bushido, surrendered, or even switched sides to survive. Personal ambition often outweighed loyalty. By the late 1800s, battlefield code gave way to pragmatism, politics, and self-preservation in the face of rapid changes.

The Samurai Class Was Wiped Out Overnight

The samurai didn’t vanish instantly. Their status eroded slowly after 1868, with the loss of tax privileges, stipends, and exclusive rights. The 1876 sword ban marked a symbolic end, but the class faded over the decades. Some adapted; others struggled with their new civilian roles.

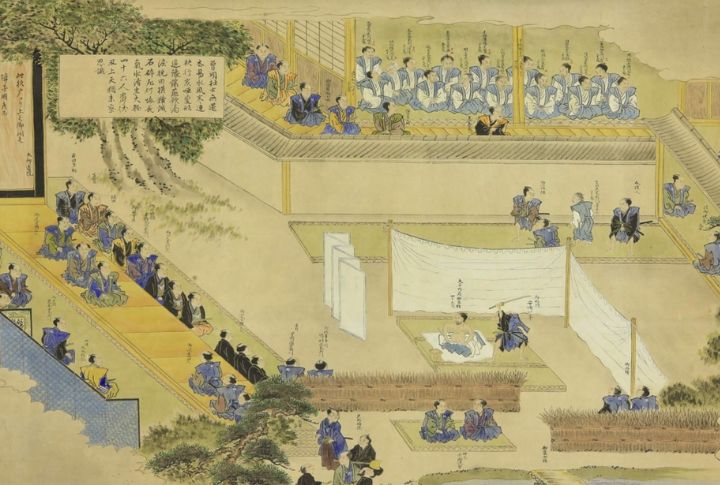

All Samurai Committed Ritual Suicide When Defeated

Ritual suicide wasn’t a universal practice. By the 19th century, it was rare and mostly ceremonial. Many samurai chose to flee, hide, or change identities. Only a few high-ranking warriors used seppuku to make a political statement—most preferred living to fight another day.

The Samurai Opposed All Modernization Efforts

Plenty of samurai embraced change. They studied abroad, joined the new military, and helped build Japan’s modern infrastructure. While some resisted, others saw modernization as a way to regain influence. Blanket resistance is a myth. In fact, many samurai went on to become engineers, teachers, and even Western-style officers.

Only Samurai Had The Right To Bear Arms

For much of the Edo period, samurai carried swords openly, but they weren’t the only ones with weapons. Samurai weren’t the only ones armed—civilians regularly carried weapons for defense. With the Meiji reforms, conscription extended formal military training to citizens of all social ranks.

Samurai Lived Luxurious And Privileged Lives Until The End

By the 1870s, many samurai were broke. The loss of government stipends forced them into farming, teaching, or begging. Privileges disappeared quickly, and former warriors had to compete in a modern economy. Some adapted well, but others never recovered from their abrupt financial collapse.

Bushido Was An Ancient Unbroken Code

The idea of bushido as a fixed warrior code comes from 20th-century nationalist writings. Earlier, samurai followed practical, evolving rules based on era or domain. Bushido wasn’t unified until long after the samurai’s political power had already faded into ceremonial status.

The Satsuma Rebellion Represented All Samurai

Led by Saigo Takamori, the Satsuma Rebellion was regional, not national. Many former samurai served in the government or opposed the revolt. While dramatic, it didn’t speak for the entire warrior class. Most samurai were split on how to respond to the Meiji reforms.

Samurai Always Served One Master Loyally

Historical records indicate that many samurai shifted allegiances during power struggles. Loyalty often depended on survival, opportunity, or better pay. Some even betrayed their lords. In the final years, loyalty to a single master gave way to domain politics and self-interest among desperate retainers.

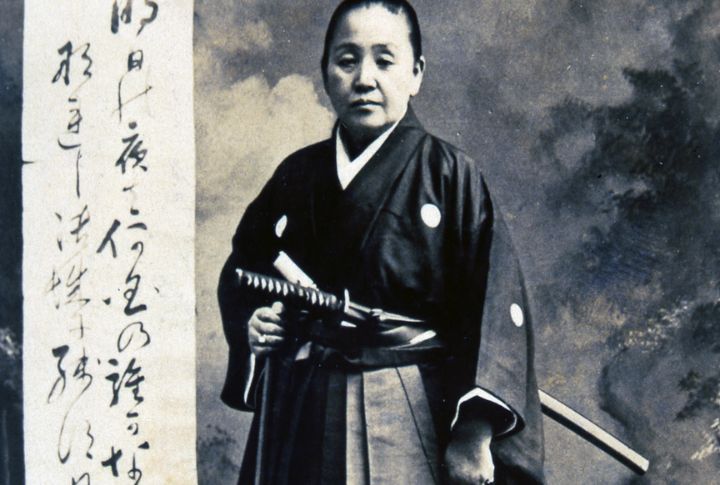

Samurai Were Always Male Warriors

While men dominated the warrior class, female samurai—known as onna-bugeisha—played critical roles in Japan’s history. Figures like Tomoe Gozen fought in battles, and many women were trained to defend their homes with weapons like the naginata. By the late samurai era, their visibility faded, but their legacy challenged the myth of a strictly male warrior tradition.