We think we know the Oregon Trail—covered wagons, long walks, and a hopeful push west. But the real hardships settlers faced were far more complex than history class ever let on. There were unexpected dangers and everyday struggles many people still don’t know; these 20 truths reveal what the journey was really like, beyond the myths.

Disease Was The Leading Cause Of Fatalities

Outbreaks like cholera claimed more lives than any ambush or accident ever did. Between 1840 and 1860, waves of illness spread quickly through wagon trains due to contaminated river water, which travelers were forced to boil before use. One traveler wrote, “You could smell the sick before you saw them.”

River Crossings Were Extremely Hazardous

River crossings posed serious dangers on the trail, especially in spring when the Platte and Snake Rivers swelled with runoff. Fast-moving currents often swept away entire wagons, claimed livestock, and destroyed supplies. Even experienced pioneers faced each crossing with fear, knowing one misstep could prove fatal.

Native American Attacks Were Less Common Than Expected

Many Indigenous tribes provided aid and trade or warned about trail conditions. Data from the 1850s shows that less than 10% of emigrant casualties involved violence. The real threat came from nature and neglect, not neighbors. False beliefs about constant danger from Native Americans quickly spread, overshadowing the true risks of the journey.

Accidental Injuries Were A Frequent Danger

Accidental injuries were a frequent and deadly danger on the trail. A single mistake while hitching a team could result in a crushed leg or even a fatal wound. Routine tasks like handling oxen or rifles often led to injuries, and with medical help far behind, these accidents could quickly turn catastrophic.

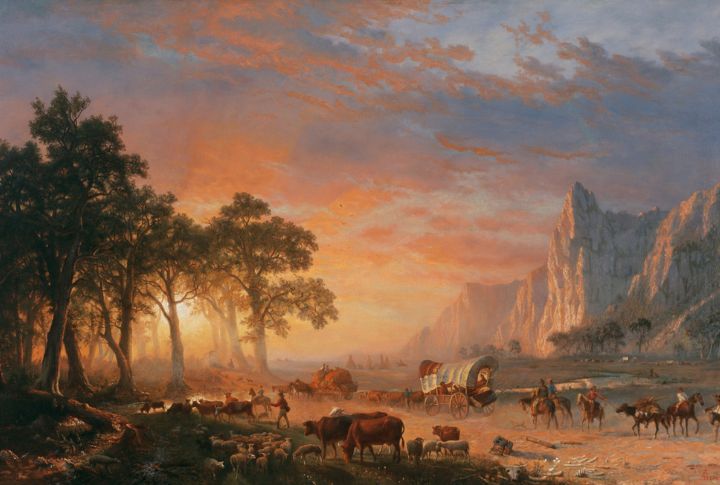

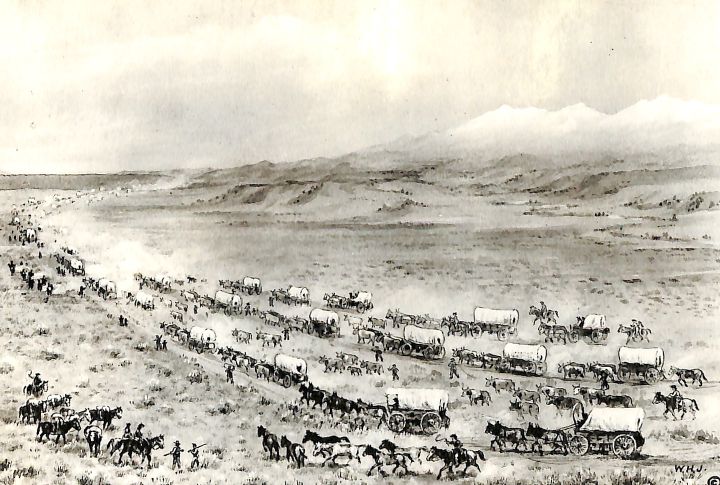

The Journey Spanned Approximately 2,000 Miles

The journey from Independence, Missouri to Oregon’s Willamette Valley stretched about 2,000 miles, passing through plains, deserts, and mountains. Without pavement or GPS, travelers relied on wheel tracks and the rising sun to mark progress. But the true challenge was enduring the grueling miles, one exhausting step at a time.

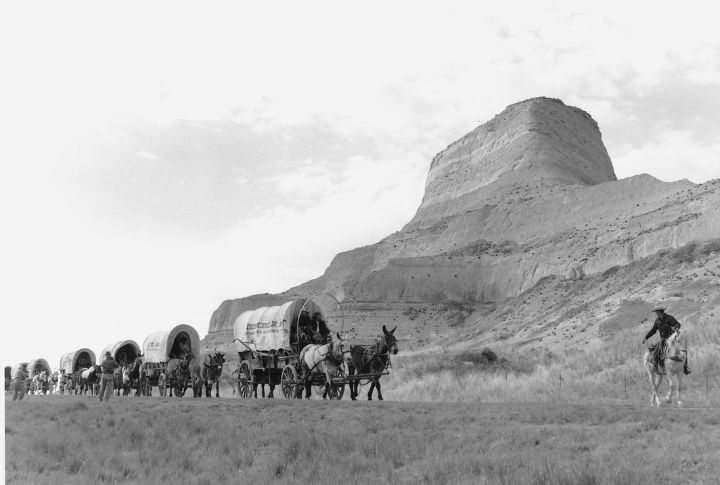

Most Travelers Used Farm Wagons, Not Conestogas

Forget the towering wagons often seen in movies—travelers needed wagons built to handle harsh terrain and frequent repairs with limited resources. Most families used small flat-bottomed farm wagons because they were lighter and easier to fix. Conestogas were simply too heavy to cross the rough terrain.

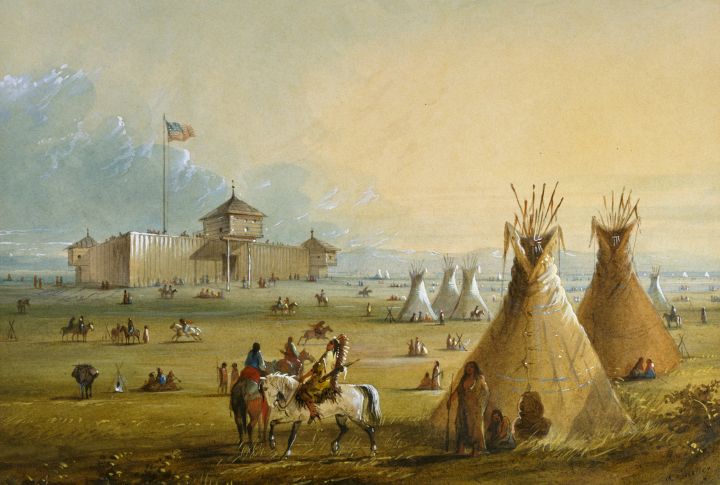

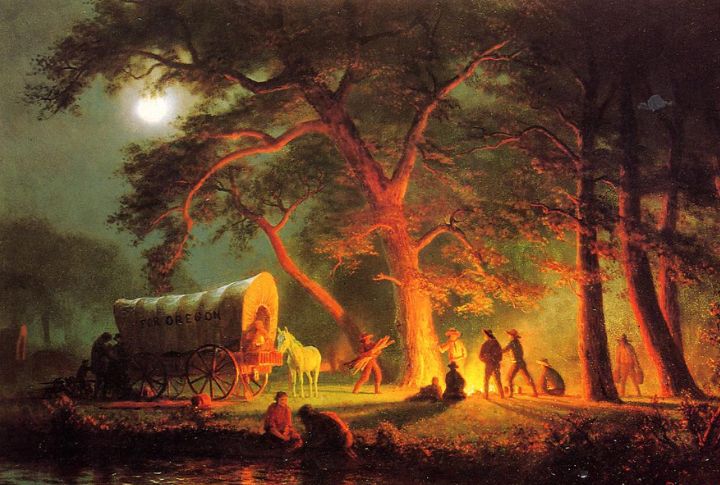

The Trail Was Initially Blazed By Fur Traders

Long before settlers headed west, fur traders were already moving through the wilderness in search of valuable pelts. Their well-worn paths that were forged through trial and trade eventually connected key outposts like Fort Laramie and Fort Hall. These early routes became the backbone of the Oregon Trail.

The Meek Cutoff Led To A Notorious Tragedy

Stephen Meek convinced over 200 wagons to follow a shortcut through Oregon’s high desert, promising faster travel. What seemed like a quick route soon turned disastrous. The unfamiliar path lacked water and clear landmarks, leading to the loss of many lives from cold and starvation.

Starvation Was A Real Threat Near The Journey’s End

As emigrants neared the end of their journey, food supplies dwindled, especially after slow mountain crossings. By the time travelers reached the Blue Mountains, many wagons had run out of provisions. Families survived on boiled leather and roots, praying to reach the Willamette Valley before the winter snow arrived.

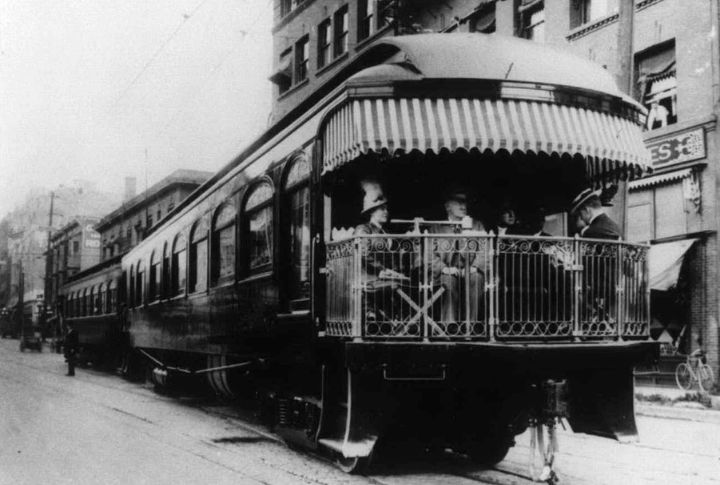

The Trail’s Decline Began With The Transcontinental Railroad

When iron rails stretched coast-to-coast in 1869, the Oregon Trail emptied almost overnight. A journey that once took six months by wagon now took just days by train. Forts were replaced by stations and oxen by tickets as the once-thriving migration route faded into a dusty memory.

The Trail Was Not A Single Defined Path

The Oregon Trail wasn’t a single, fixed path. Instead, travelers navigated multiple cutoffs and reroutes to avoid floods, find better grazing, or bypass difficult terrain. Conditions like the Platte River and Barlow Road influenced these changes, making the route adaptable to the constantly shifting needs of the emigrants.

The Journey Typically Took Four To Six Months

Families walked an average of 15 miles each day, often starting in late April to beat the winter snow. Because the entire trip was on foot, storms or illness could easily slow progress. Moving too fast damaged wagons, which caused more delays. As a result, a steady pace became the safest strategy.

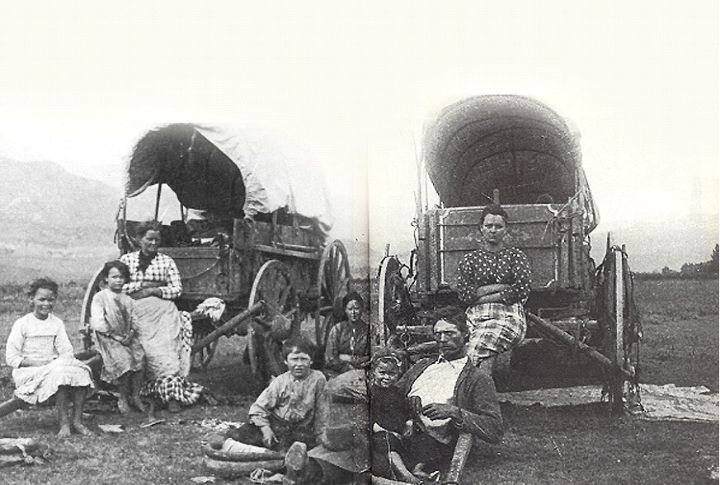

Women Played A Vital Role On The Trail

Throughout the grueling journey west, women were the backbone of daily survival, managing meals and providing medical care. They calmed livestock that were giving birth and recorded hardships in journals. One woman even made a dress from wagon canvas after losing her belongings in a river. Their resilience held families together.

Children Faced Unique Dangers

Unlike modern childhoods filled with play, life on the trail demanded grit from even the youngest travelers. Children walked most of the way, collected buffalo chips for fires, and helped manage the animals. Along the route, many suffered injuries or mourned lost siblings; they were left facing the miles with blistered feet and heavy hearts.

The Trail Inspired A Popular Educational Video Game

The educational video game The Oregon Trail, released in 1971, became a classroom favorite by turning frontier survival challenges into interactive lessons. Students learned to manage oxen, handle food shortages, and fix broken wagons. These hardships became a rite of passage in computer labs.

The Journey Was A Test Of Endurance And Resilience

Many families didn’t reach Oregon, but each proved something about human endurance. They carried babies, buried relatives, and climbed cliffs with no guarantees. If your great-great-grandparents made it, they didn’t just survive; they became part of history, moving forward one creaking wheel at a time.

Accidental Shootings Were A Frequent Hazard

Loading rifles while riding in a moving wagon was a common but risky task. A bump or improperly packed musket could result in tragedy. For example, one man accidentally shot himself while trying to untangle his bedroll. Although guns were used for defense, they were weapons that could go off unexpectedly.

Supply Shortages Were Common

Supply shortages were common on the trail. Barrels ran dry, flour molded, coffee disappeared, and food ran out before they reached Nebraska. Traders charged high prices at forts, knowing travelers had no choice. Your wagon’s weight limit determined the food you carried and miscalculations led to hunger.

Rattlesnake Bites Added To The Perils

Rattlesnake bites posed a constant threat as sharp fangs struck from beneath rocks or grass, especially on sun-warmed paths. Campfires didn’t always keep the snakes away and barefoot children were often the first victims. Without antivenom, survival depended on luck, rest, and the arrival of help.

Weather Extremes Posed Constant Challenges

Relentless heat waves baked the land for weeks. Hailstorms and blizzards often struck without warning, shattering trees and causing widespread damage. For travelers, extreme weather was more than an inconvenience; it was a significant challenge. One journal described the skies as “meaner than any outlaw.”