When Earth turns hostile—frozen, boiling, salt-choked, or starved of light—most creatures vanish. But not these. They don’t merely endure. They flourish. From high-altitude spiders to worms living beneath the seafloor, these organisms redefine what “livable” means. One even walked off a space mission like it was no big deal.

Mountain Stone Weta

Freeze it solid, and it won’t blink—because it can’t. This large New Zealand insect survives complete ice entombment, halting all vital functions until thawed by spring. It’s not just tough; it’s the largest known insect to pull off this frozen hibernation trick and hop away like it never happened.

Himalayan Jumping Spider

At 22,000 feet on Everest, this spider stalks windblown insects among bare rocks. Its scientific name translates to “the one who survives above all,” and it earns it—no oxygen tanks, no shelter. Just legs, cold air, and a vertical hunting ground most life refuses to touch.

West African Lungfish

When water vanishes, it doesn’t panic—it digs. The lungfish buries itself in mud and wraps in a mucus shell, waiting out droughts that can last half a decade. Breathing through an ancient lung and barely moving, it holds out until the rains finally return.

Red Flat Bark Beetle

Subarctic winters won’t kill this beetle. Its secret? A body that vitrifies—turns glasslike—at temperatures plunging to –148°F. With glycerol and antifreeze proteins coursing through it, the beetle goes stiff, then resumes crawling once the ice melts. No frostbite, no fuss.

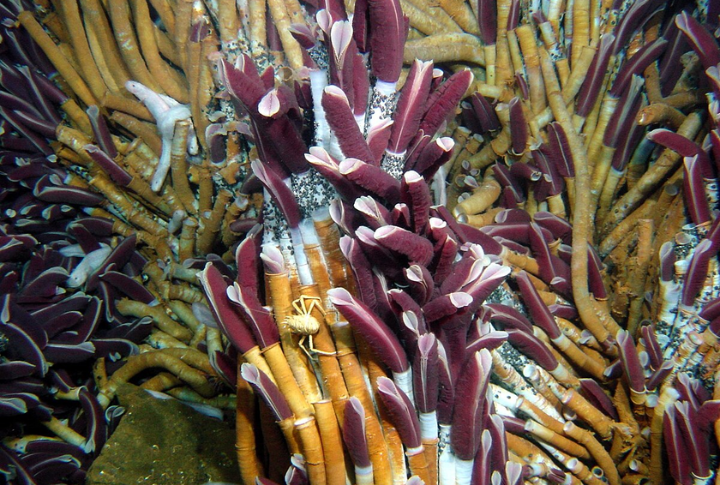

Tube Worm Cities Beneath the Sea

Near hydrothermal vents, these giant worms form towering colonies in black, sulfurous plumes. With no mouths or digestive systems, they rely entirely on internal bacteria to convert vent chemicals into food. They anchor bustling underwater communities in places that seem purpose-built to erase life.

Tardigrade

Microscopic and absurdly durable, the tardigrade shuts itself down into a desiccated pellet when threatened. It’s shrugged off boiling water, radiation, and even space vacuum. Revive it with moisture, and it picks up right where it left off—like nothing ever happened.

Ice Crawler

Most insects flee from cold. This one dies from heat. Ice crawlers cling to glacier margins, foraging on frozen carcasses and avoiding direct sunlight. Anything warmer than 50°F becomes lethal. They don’t tolerate the cold—they require it to function.

Spectacled Eider

Rather than migrate, these sea ducks hunker down in the Bering Sea through Arctic winter. They dive under solid ice for mollusks, gathering in dense groups at the tiniest ice gaps. Wind chills are brutal, darkness is constant—and they seem perfectly content.

Hydrothermal Vent Shrimp

These deep-sea shrimp perch beside scorching volcanic vents, navigating fine thermal boundaries that separate livable warmth from instant death. They carry microbial hitchhikers on their shells that may help digest chemicals in the water. It’s dinner, served hot and acidic.

Siberian Salamander

One individual spent over ten years entombed in frozen soil—then defrosted and slithered away. This amphibian produces cryoprotectants that shield its cells during deep freezes. It doesn’t just survive cold; it rides it out like a long nap, waking up ready to breed.

Desert Toad

Rain is rare in the desert, but when it comes, desert toads explode into action. After years buried underground, they surface overnight, mate, lay eggs, and vanish again—often before the puddles disappear. It’s a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it breeding frenzy calibrated to unpredictable weather.

Giant Tube Worm

No mouth, no stomach, no sunlight—and no problem. These towering worms use internal bacteria to convert hydrogen sulfide into energy, thriving over a mile below the surface. Some reach 8 feet in length, growing faster than many surface-dwelling species despite never seeing the sky.

Devil Worm

First discovered in a South African gold mine, this microscopic nematode thrives over a mile belowground in hot, high-pressure rock fissures. Temperatures hover around 122°F. It’s one of the deepest animals ever found, living in geological cracks few thought life could reach.

Saharan Silver Ant

These ants bolt across sand that scorches at 150°F. They’re built for it—light-bouncing body hairs, heat-resistant feet, and uncanny navigational skills help them scavenge in short, deadly windows. If they don’t move fast enough, they cook. So they don’t slow down.

Brine Shrimp

In waters saltier than the ocean, these tiny crustaceans thrive where nearly everything else dies. Their cells excrete salt, their blood brims with hemoglobin, and their pink blooms turn entire lakes opaque. Flamingos feast on them. Other creatures avoid the briny wastelands entirely.

Pompeii Worm

Water pouring from hydrothermal vents can hit 176°F, yet these worms cling nearby. Their backs host dense colonies of heat-tolerant bacteria that may insulate them from extreme temperatures. Few animals tolerate such proximity to underwater volcanoes, let alone build homes on them.

Subseafloor Creatures

In 2024, researchers found mussels and tube worms thriving beneath the ocean floor—beneath the vents, beneath the sediment. This hidden community lives in slow, chemical symbiosis in a world without light or oxygen. It’s not just deep sea—it’s beneath deep sea.

Antarctic Icefish

These pale fish swim with antifreeze proteins in their blood and no hemoglobin at all. In the frigid Southern Ocean, their near-clear blood flows just enough to keep them alive. No other vertebrate pulls off this kind of cold-blooded endurance.

Thermophilic Archaea

Technically microbes, Pyrolobus fumarii survive in vent water at 235°F. That’s hotter than most autoclaves. Their enzymes remain stable under thermal assault that would destroy anything else. They prove life’s limit hasn’t been reached—just that our definitions were too narrow.