Dire wolves weren’t just bigger gray wolves with flashier teeth. They evolved along a separate path, shaped by specific prey, climate, and physical design. Heavier bodies and limited adaptability made them powerful but less flexible. Here’s a look at ten traits that gave dire wolves their own identity in the prehistoric world.

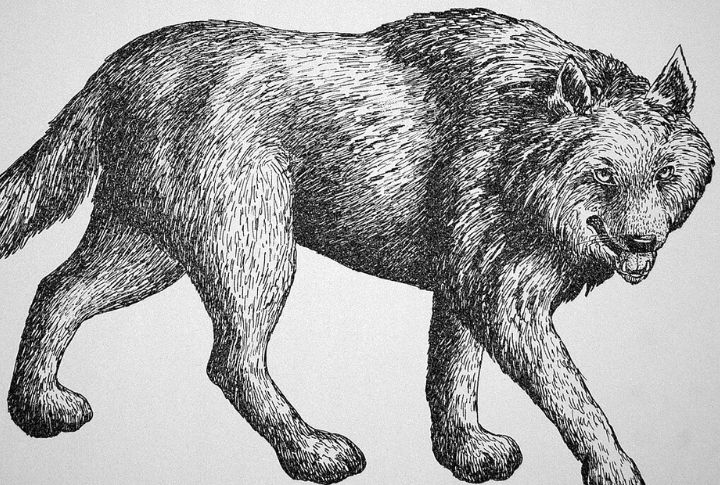

Overall Body Structure And Mass

Compared to gray wolves, dire wolves were tanks. Heavier frames and thicker bones gave them a brute force advantage. It worked great on large Ice Age creatures. Speed, though? Not their thing. These predators weren’t chasing down prey across open fields, they were meeting it head-on with muscle and grit.

Limited Geographic Range Across The Continent

Unlike gray wolves, which thrived in a broad range of climates, dire wolves mostly inhabited warmer regions of North and South America. This limited geographic range meant they struggled to survive when colder Ice Age environments shifted drastically near the Pleistocene’s end.

Tooth Strength And Functionality

These predators had jaws built like wrecking balls. While gray wolves sliced through flesh, dire wolves crushed bones with ease. Their feeding style was entirely different—designed to tear into big game and maybe scavenge what others ignored. For them, bone-cracking wasn’t just brutal; it was survival.

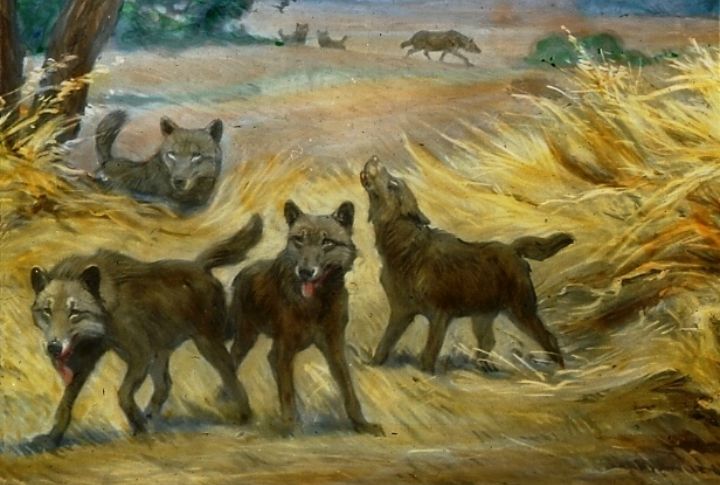

Social Structure And Hunting Cooperation

Gray wolves are known for their intricate pack cooperation, but evidence suggests dire wolves followed a simpler social structure. They likely hunted in smaller groups or pairs, limiting their ability to chase down swift or elusive prey. This made their hunting strategy less adaptable across changing environments.

Skull Shape And Snout Proportions

Dire wolves had shorter, broader snouts compared to gray wolves, giving their skulls a more robust and compact profile. This wider structure offered a stronger anchor for jaw muscles, enhancing bite force. The adaptation reveals how evolution favored brute power over streamlined efficiency in their predatory strategy.

Reproductive Rate And Pack Behavior

Raising pups wasn’t a rapid process for dire wolves. Studies of ancient dens show they reproduced more slowly than gray wolves. That slower pace likely stalled recovery after environmental stress, leaving their numbers thin during lean years. Over time, fewer litters meant fewer chances to keep the species going.

Speed And Endurance Capabilities

Speed wasn’t the strong suit of dire wolves. The heavier bodies and shorter legs made long-distance chases inefficient. Instead, they likely hunted with quick ambushes or sudden sprints, a hunting method that stands in sharp contrast to the endurance-based pursuits gray wolves are known for.

Extinction Timing And Competitive Displacement

While gray wolves adapted and survived past the Ice Age, dire wolves didn’t. As the climate shifted and prey dwindled, competition with more adaptable canids—including gray wolves and coyotes—intensified. The dire wolf’s slower reproduction and rigid ecological niche couldn’t keep pace, sealing its extinction about 10,000 years ago.

Inner Ear Structure And Balance Control

Inside the skull, the story shifts again. Dire wolves had different inner ear bones than gray wolves, which hint at unique ways of balancing and moving their heads. These changes probably helped them manage their heavier build and matched the brute-force style they used to take down prey.

Hybridization Limitations With Other Canids

Their DNA ran solo. Dire wolves were genetically isolated, never crossbreeding with coyotes or gray wolves. That wall around the gene pool kept adaptations out; traits that might’ve helped during rapid environmental shifts. In a changing world, that genetic rigidity likely sped up their fall.