WWI remains one of history’s most significant and transformative events. However, certain misconceptions about the war’s realities have distorted our understanding over time. These myths continue to shape how we view the war’s impact. So, it’s time to examine the wrong statements and get a clearer view of the war’s true nature and lasting global consequences.

WWI Was Inevitable

Diplomacy didn’t collapse overnight. While militarism and alliances raised tensions, war wasn’t guaranteed. In July 1914, choices by Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Russia escalated a local-global conflict. The outbreak resulted from specific decisions rather than an unstoppable chain of events.

Most Troops Were Killed

Millions fought, but the truth is that many returned home. Britain, for instance, mobilized 7,500,000 and lost over 692,065. Infantry faced grave risks, yet survival was far more common than often claimed. The myth endures partly because large-scale casualties can misshape public understanding of actual survival rates.

The Rich Commanded, The Poor Died

Enlisted men and officers came from varied social classes. British junior officers, many from elite schools, suffered exceptionally high mortality—over 17 percent in some regiments. These young leaders were often tasked with leading assaults, which placed them at the front of danger and frequently among the first to fall.

It Was All Fought In France and Belgium

The Western Front dominated headlines, but action spanned continents. From East Africa to Gallipoli and Mesopotamia, combat reached colonies and remote locations. The campaigns involved local communities and strained supply lines, all of which led to shifts in political control that influenced the postwar world.

Men Were Stuck In Trenches

Trenches mattered, but they weren’t permanent cages. Soldiers rotated between frontline duty and rear areas for recovery or support. Campaigns like the Battle of the Somme included movements across open ground. Mobility returned, especially in 1918, as new tactics broke the deadlock dramatically.

No One Won

The Central Powers collapsed under military defeats and economic pressure. Germany’s major attacks in the spring of 1918 failed, and Allied advances forced an armistice. Victory was actually achieved through tangible factors, including material superiority and coordinated operations, which produced clear and decisive results.

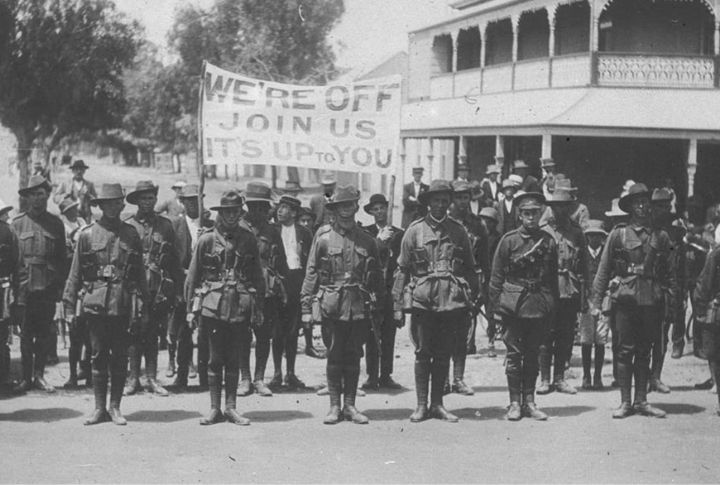

All Soldiers Were Draftees

Many volunteered to join the war. Britain relied solely on volunteers until 1916, when conscription became necessary. In Australia and Canada, forced enlistment triggered widespread protest and political fallout. Recruitment varied across regions, shaped by local identity and each nation’s distinct approach to military obligation.

America Ended The War Alone

U.S. involvement mattered, but Allied endurance from 1914 to 1917 laid the foundation. By 1918, American troops arrived in large numbers, tipping the balance. Still, victory depended on cooperation across fronts, with support from France and Britain playing a critical role in the outcome.

Soldiers Didn’t Understand The War

Soldiers knew why they were fighting. Motivations included a sense of national pride or personal obligation. Frontline combatants recognized the stakes, even amid disillusionment. Memoirs reflect that many understood their role and remained committed, even as the war’s realities challenged their expectations.

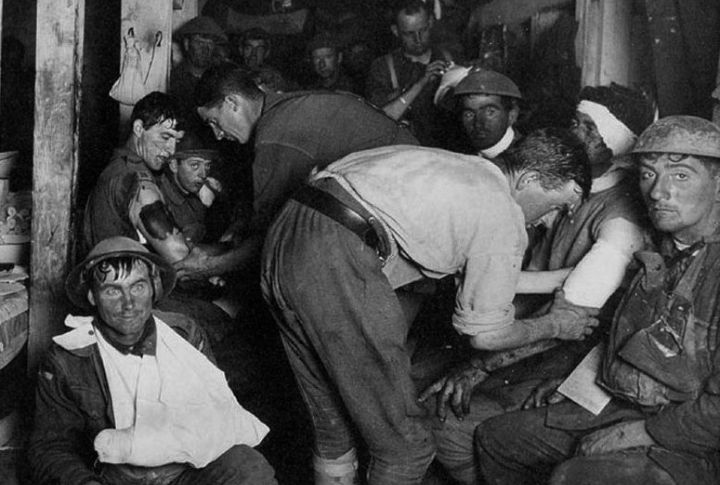

Shell Shock Meant Cowardice

Early responses misunderstood psychological trauma, but by 1917, military medicine began addressing combat stress seriously. Treatments included rest centers and specialist care. Shell shock wasn’t weakness—it was a response to unrelenting exposure. Today’s PTSD research owes much to these early wartime observations.