You might imagine an author closing the final page of their manuscript with a sigh of relief, never daring to revisit it again. But for some, the story doesn’t end at publication—it just goes on a long intermission. Years later, they return with a red pen (or keyboard) in hand, ready to rewrite history. So, here are 10 fascinating examples of stories that didn’t stay the same.

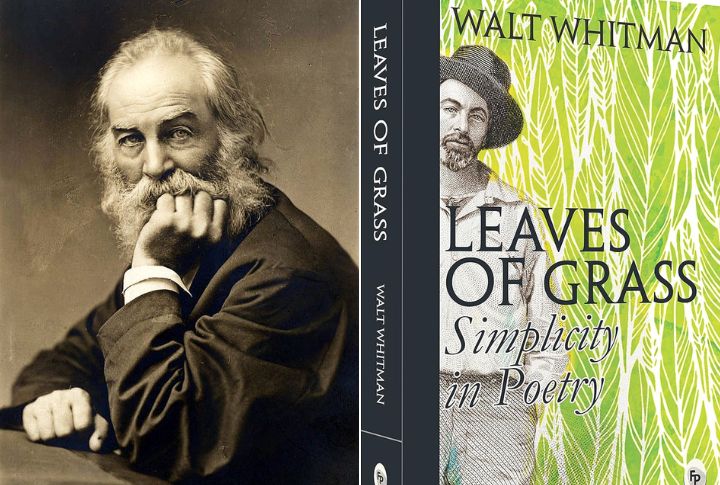

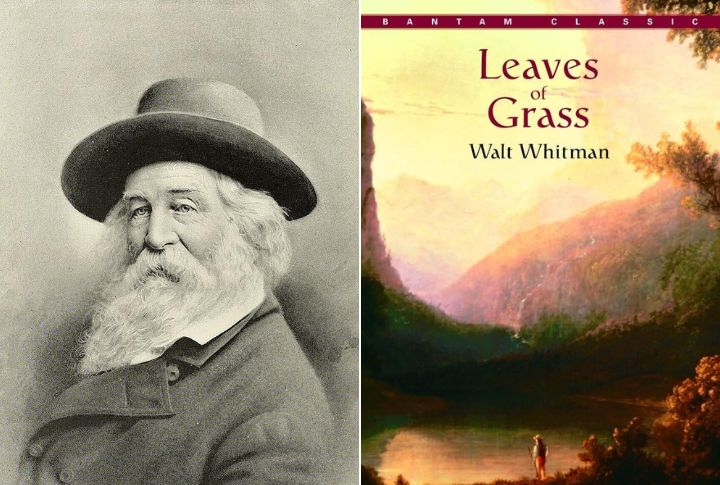

“Leaves Of Grass” By Walt Whitman

First published in 1855, “Leaves of Grass” began as a modest experiment in free verse. Walt Whitman kept returning to it, revising and expanding through six or nine editions over 37 years. Each version mirrored his evolving ideals, until the final, massive edition stood as his lifelong self-portrait in poetry.

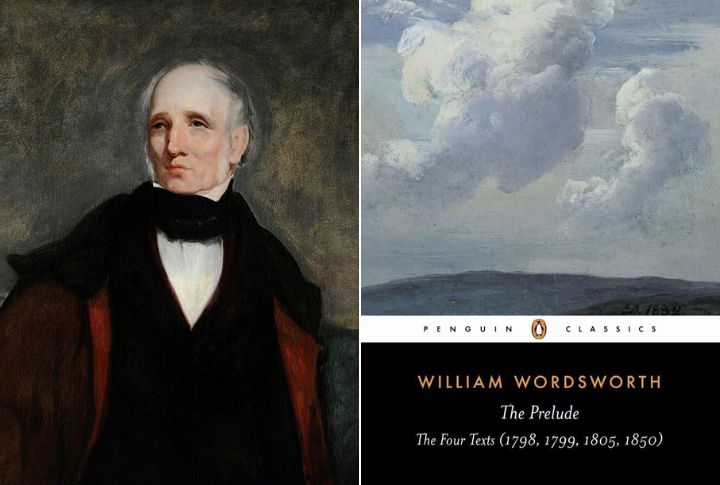

“The Prelude” By William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” began in 1798 as a youthful exploration of self and nature. Years of reworking transformed it into a richer, more contemplative masterpiece. Published in 1850 after his death, the poem charts his personal journey from early enthusiasm to mature philosophical depth.

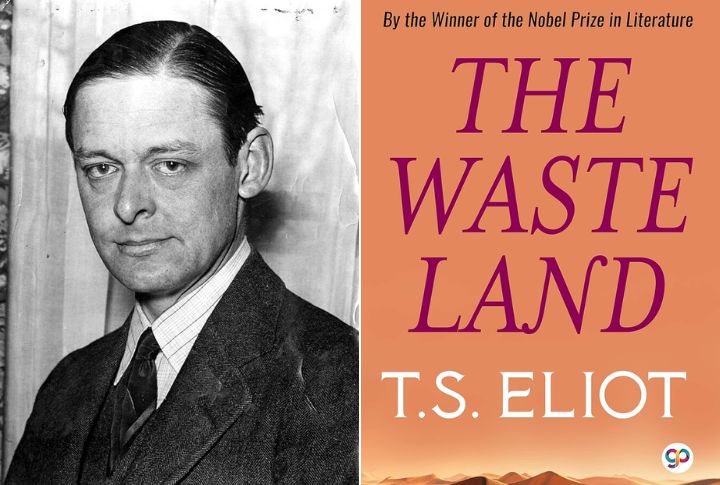

“The Waste Land” By T.S. Eliot

In 1921, “The Waste Land” existed as a lengthy, loosely structured manuscript. Ezra Pound’s incisive edits cut it down to a taut, groundbreaking work. T.S. Eliot would later include notes and subtle adjustments, yet always credited Pound’s input as the defining force behind the poem’s enduring power.

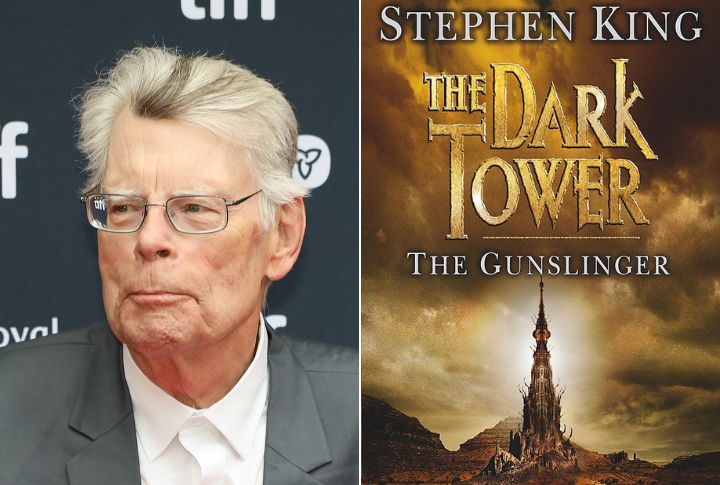

“The Gunslinger” By Stephen King

The first chapter of “The Dark Tower” saga, “The Gunslinger,” hit the shelves in 1982, but Stephen King wasn’t done with it. In 2003, he gave it a full narrative tune-up—fixing inconsistencies, sharpening characters, and tightening language—to ensure the series began with maximum impact.

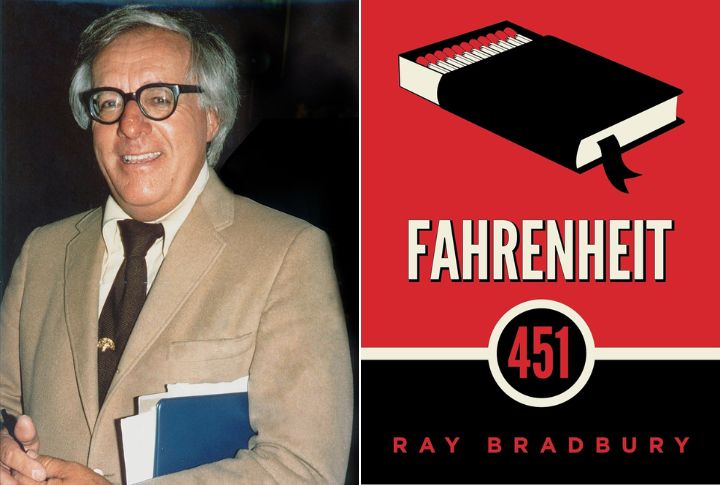

“Fahrenheit 451” By Ray Bradbury

“Fahrenheit 451” started in 1953 as Bradbury’s sharp jab at censorship. Then came a coda that tackled the subject head-on, plus updated technological references to match the times. Each tweak kept it buzzing with relevance, tracking his shifting worries about the world outside its pages.

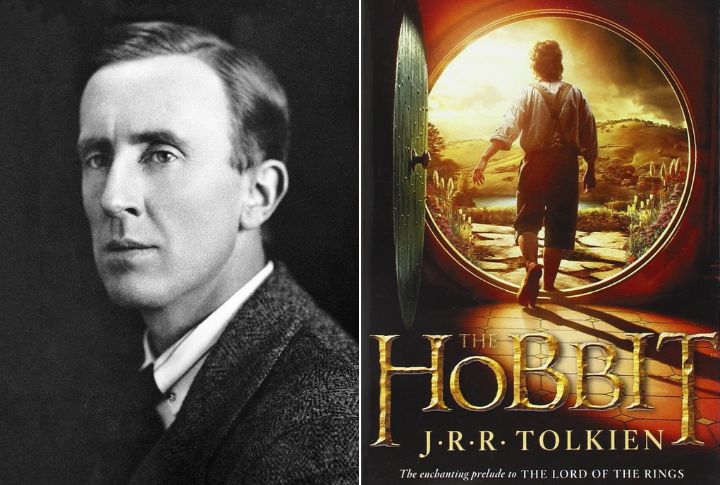

“The Hobbit” By J.R.R. Tolkien

When “The Hobbit” first appeared in 1937, it told a breezier tale with a friendlier Gollum. Tolkien’s rewrites, made after crafting “The Lord of the Rings,” expanded the Ring’s power, deepened the shadows, and aligned the adventure into a tightly woven, fully cohesive Middle-earth saga with far-reaching consequences.

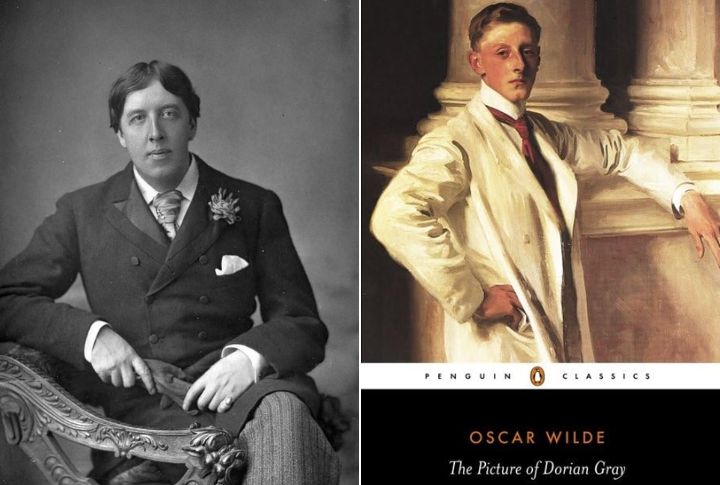

“The Picture Of Dorian Gray” By Oscar Wilde

The first printing in 1890 sparked outrage, as it was considered too indecent for the era. A year later, Oscar Wilde returned with more chapters and a gentler approach, while letting Dorian’s fall unfold with greater care. These changes disarmed critics without stripping the tale of its dark charm.

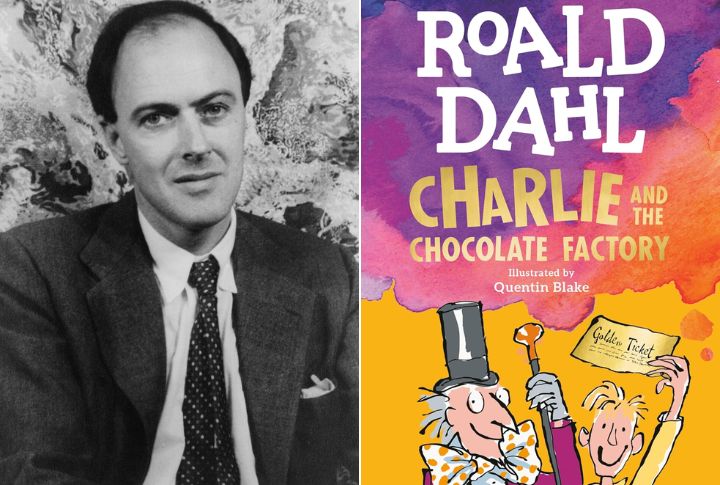

“Charlie And The Chocolate Factory” By Roald Dahl

In 2023, Puffin Books decided “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” needed a softer vocabulary. Gone were “fat” and “ugly,” with Augustus Gloop now described as “enormous.” Sensitivity readers helped shape these edits. Yet the changes ignited debate, which in turn prompted Puffin to stock shelves with both updated and original versions.

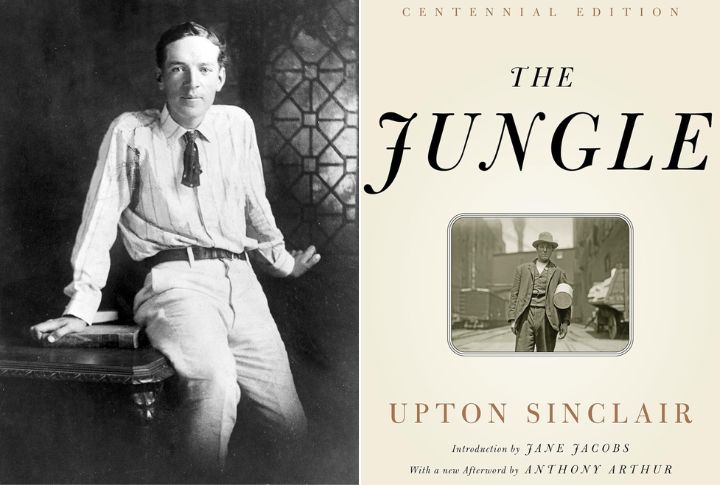

“The Jungle” By Upton Sinclair

Back in 1906, “The Jungle” came in swinging at labor abuses. Then, the edits arrived. Out went the nightmare fuel, and in came political hot takes and reform history. Sinclair basically kept serving new cuts like a director who refuses to stop dropping sequels.

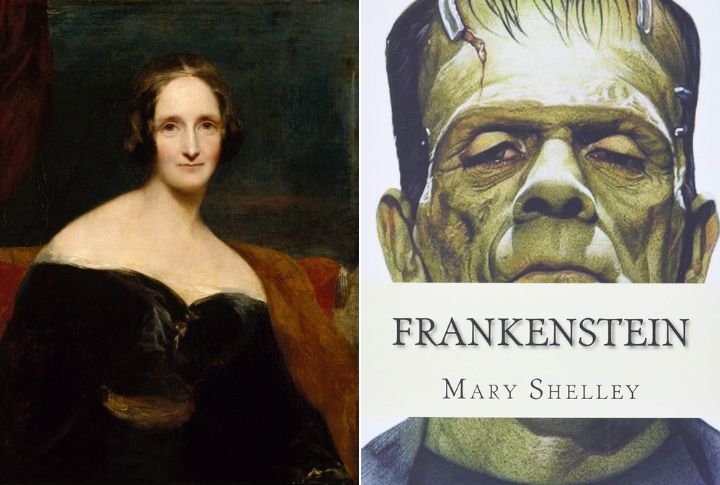

“Frankenstein” By Mary Shelley

What changes when a gothic story gets rewritten? The 1818 “Frankenstein” was bold and grim. However, in 1831, Mary Shelley made it more thoughtful, toned down Victor’s pride, and explained her inspiration in a new preface. The result was a richer tale about ambition and its consequences.