Before steamships ever reached Japanese shores, the silence had already been broken. European visitors—traders, friars, envoys—had quietly tested Japan’s openness. Sometimes, they were welcomed. Often, they weren’t. But their presence didn’t go unnoticed. This list reveals 10 early missions that significantly influenced Japan’s perception of the West long before the arrival of Americans.

Portuguese Merchants Land At Tanegashima (1543)

A drifting Portuguese vessel reached Tanegashima in 1543, carrying not just traders but something that caught Japan’s attention: firearms. The arquebus spread quickly, reshaping local warfare and strategy. As interest surged, samurai across the islands began training with it. That unplanned landing quietly launched Japan’s relationship with European technology.

Jesuit Francis Xavier Arrives In Kagoshima (1549)

Francis Xavier stepped ashore with a mission in mind and adjusted quickly to Japan’s unfamiliar rhythms. He gained an audience with the Satsuma daimyo and began planting Christian roots. By describing local customs in his letters, he helped Europe understand Japan and gave missionaries a reference point for future efforts.

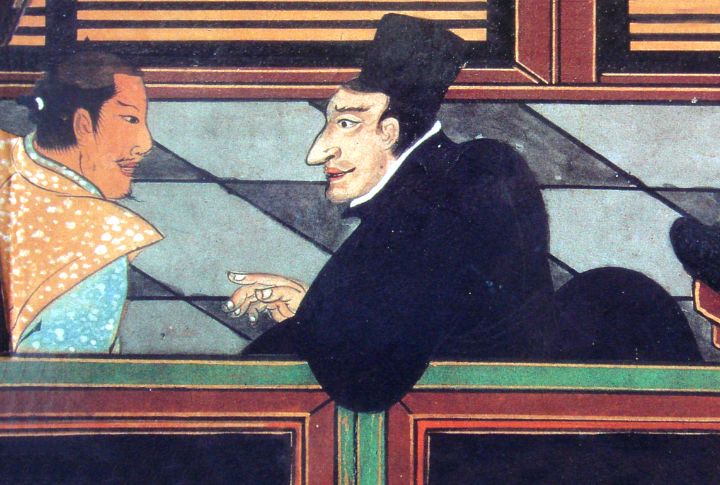

Portuguese Priest Luis Frois Meets Oda Nobunaga (1569)

Frois didn’t just preach, he documented. His meetings with Nobunaga offered him protection and a rare vantage point inside Japan’s shifting politics. Despite Buddhist resistance, Nobunaga tolerated the mission. Frois’s detailed writings now serve as some of the richest surviving records of Japan during the Sengoku period.

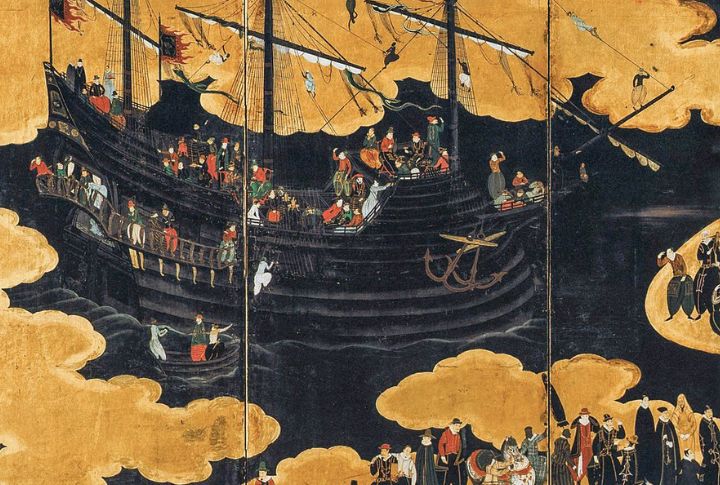

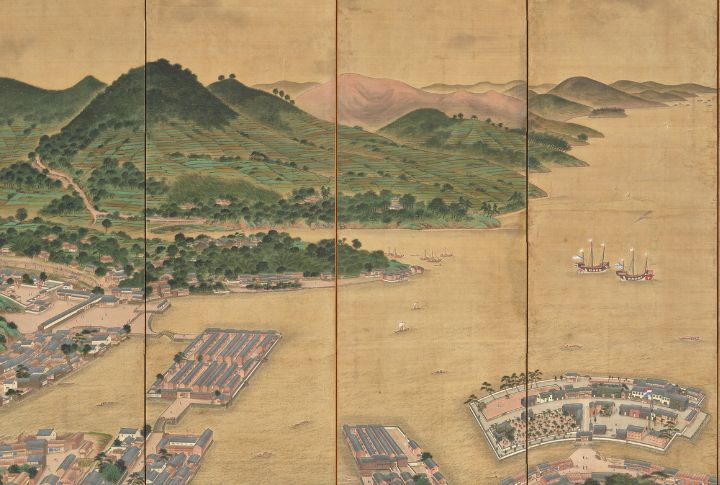

Portuguese Establish Nagasaki Trading Post (1571)

The city became more than a port once Nagasaki opened to Portuguese traders. After a powerful convert granted land to Jesuits, commerce and religion fused into daily life. Over time, Nagasaki developed a distinct identity shaped by Catholic influence and foreign exchange, which offered Japan its first real window into Europe.

Italian Jesuit Organtino Establishes Seminary In Kyoto (1576)

Education became a quiet bridge. Jesuit priest Organtino helped set up a seminary in Kyoto where young Japanese converts were trained. The school became a hub of cultural exchange, mixing theology and possibly even European art. Through this, the Jesuits introduced ideas that stretched far beyond religion.

Jesuit Printing Press Arrives In Japan (1590)

Printing changed the pace of the mission. When Jesuits introduced movable type from Goa, they began producing texts in Romanized Japanese. These weren’t just religious pamphlets. They included moral plays, theological works, and dictionaries. The press helped solidify Christian teachings and introduced new modes of learning into Japanese society.

Spanish Franciscan Missions Reach Kyoto (1594)

By the late 1500s, Franciscans had entered Kyoto’s bustling heart, stepping into a space already touched by Jesuits. Their presence stirred competition and brought new diplomatic gestures. Though details are hazy, records suggest bold claims and gift-giving aimed at winning influence. These efforts reflected Spain’s quiet ambition to sway Japan.

Dutch Sail Into Hirado (1609)

When the Dutch arrived in Hirado, they secured official trading rights from the Tokugawa shogunate—an edge few others managed. Instead of preaching, they focused strictly on commerce, likely bringing exotic goods such as clocks. That practical approach helped them stay, eventually becoming Japan’s only European partner under sakoku.

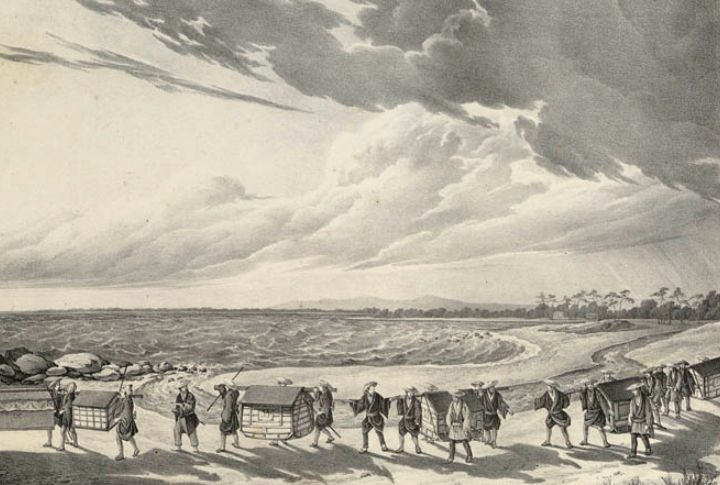

Christian Daimyo Send Embassy To Europe (1582)

The Tensho Boys’ Embassy was Japan’s first official step toward Europe. Four young envoys, sent by Christian daimyo, traveled as far as Rome, where they met the Pope and European leaders. Their journey sparked fascination abroad, and they likely returned with items that hinted at Europe’s cultural and scientific reach.

Portuguese-Japanese Mixed-Race Community Emerges In Nagasaki

Trade led to connection, and connection led to community. In Nagasaki, intermarriage between locals and Portuguese created a small but significant mixed-race population. Many children became bilingual and acted as translators or go-betweens. Referred to as “Namban-jin,” they played a quiet but essential role in daily cross-cultural life.