The Civil Rights movement remains a defining chapter in American history, but interpretation evolves as new questions arise. Scholars use different structures to trace long-term struggles, regional differences, cultural forces, and debates within the movement. Each approach given below reshapes the narrative’s outline without altering its factual core.

Long Civil Rights Movement

This approach extends the Civil Rights timeline far beyond the 1950s and 1960s, showing how the fight for equality grew out of earlier battles stretching back to Reconstruction. It links voting rights, labor organizing, women’s activism, and anti-lynching campaigns into one continuous movement rather than a brief mid-century moment.

Cyclical Recurrence Model

This framework says the Civil Rights movement didn’t happen out of nowhere. Instead, the country goes through repeating phases: people push for change, others push back, and then a new wave of activism rises again. The model argues that the Civil Rights era was one round in this ongoing cycle of progress and resistance.

Episodic Vs. Linear Debate

Once the timeline is set, a writer still needs a structure. Some choose episodic storytelling, which highlights sharp, dramatic moments like the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Others build a linear story that follows change gradually. Each option guides the reader toward either high-impact scenes or a continuous unfolding.

Intersectional Framework

Some storytellers use an approach called intersectionality, a term coined by scholar Kimberle Crenshaw to describe how different parts of a person’s identity shape their experiences. When this lens guides the narrative, the story makes space for women, LGBTQ+ participants, and others who were often overlooked in earlier accounts.

Economic Justice Emphasis

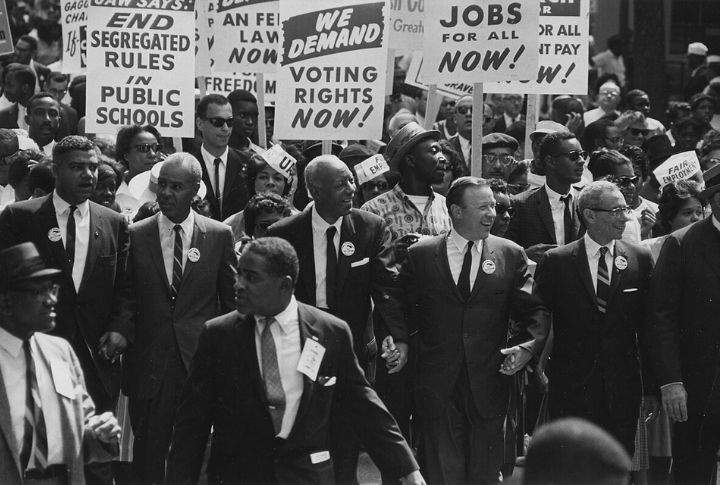

A writer can also build the entire story around economic demands. This view explains the era by showing how wages and basic financial security fueled major demands. It also clarifies why the March on Washington of 1963 carried the full title “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.”

Youth And Student Agency

One powerful way to frame the era is to show how much of the movement’s spark came from young people. College students organized sit-ins and marches, and high schoolers ran voter drives. By placing them at the center, the story gains urgency and a sense of fearless experimentation.

Regional Variations

The story can also be organized by geography, which helps readers understand why the movement looked different from place to place. Northern cities battled unfair housing and aggressive policing, while Southern communities fought legal segregation. This map-based structure lets the narrative shift tone as the locations change.

Nonviolence Vs. Self-Defense Debate

Another storytelling path focuses on the disagreement over tactics. Martin Luther King Jr. pushed nonviolence as a moral strategy, while groups like the Deacons for Defense argued that armed protection kept people alive. Exploring this tension helps the writer explain why the movement never relied on a single approach.

Grassroots-Centered Lens

Some writers choose to start small—on front porches, in church basements, or inside neighborhood groups—because so many turning points began at that level. This angle shows how ordinary people built momentum long before national leaders emerged, giving the story a more personal, community-driven feel.

Cultural Production Role

A narrative can grow from the creative voices of the era, since many people understood the movement through songs and artwork rather than speeches. “We Shall Overcome,” for example, worked like a unifying message. When culture leads the storytelling, readers grasp the mood behind the struggle.