History books and folklore are filled with names that feel like larger-than-life figures we grew up believing were as real as any ruler or warrior. Yet many of these characters were never flesh and blood at all. Some were born in poetry, others in propaganda, and a few from outright imagination. This list pulls back the curtain on 20 such figures, revealing how myth often masquerades as history.

King Arthur

King Arthur was depicted as the noble leader of the Knights of the Round Table, capturing the imaginations of people for centuries. Early mentions appear in Welsh chronicles, but no contemporary records confirm the existence of this king, despite the famous stories of his valor.

Robin Hood

The outlaw hero famed for “robbing from the rich and giving to the poor” emerges from 14th-century English ballads. While several historical candidates have been proposed, none match the folk hero of legend. Over time, Robin Hood evolved into a symbol of justice and social morality.

Mulan

Celebrated in the Chinese “Ballad of Mulan,” she is said to have disguised herself as a man to take her father’s place in war. Despite her legendary heroism and embodiment of filial piety, there are no historical records to verify her existence. Likely, Mulan represents a fusion of folk tales and archetypal virtues.

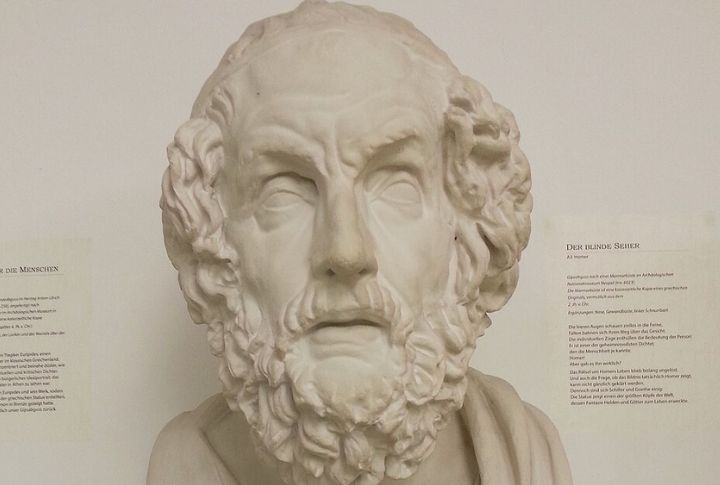

Homer

The epic poems “Iliad” and “Odyssey” are traditionally attributed to Homer, yet his identity remains shrouded in mystery. Many scholars suggest “Homer” represents a long-standing oral tradition rather than a single individual. Details about his life and birthplace lack reliable evidence.

Betty Crocker

Introduced in 1921 by the Washburn Crosby Company, this figure was invented to promote recipes and packaged mixes. She was a carefully crafted persona, with multiple “faces” chosen by staff over the decades. Over time, she became a trusted cultural symbol of home cooking and domestic know-how in America.

Uncle Sam

Uncle Sam became the symbol of the U.S., recognized by his star-spangled suit and tall top hat. Inspired in part by Samuel Wilson, a man who packed meat during the War of 1812, he was never a real person. In 1961, he was officially adopted as a national emblem and recruitment icon.

Prester John

In medieval Europe, people talked of Prester John, a mighty Christian ruler said to govern an Eastern empire. His supposed kingdom promised hope of an ally against Islamic powers. The legend of this king also inspired Columbus and Vasco da Gama.

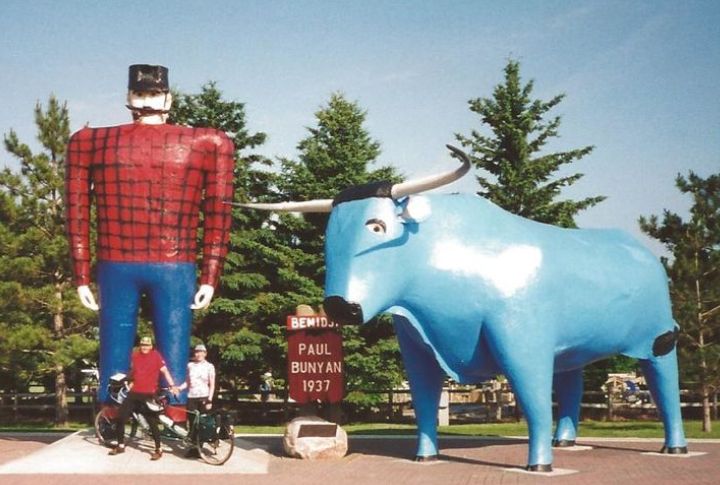

Paul Bunyan

This colossal lumberjack is said to have reshaped forests and rivers with his strength. Alongside his faithful blue ox, Babe, he symbolized the grit of frontier logging life. Yet his legend was less folklore than marketing, which logging companies popularized in the 20th century.

Pope Joan

According to medieval stories, Pope Joan disguised herself as a man and secretly ruled the Catholic Church in the 9th century. Her supposed reign fascinated Europe for centuries, often serving as satire against papal authority. However, church records reveal no trace of her.

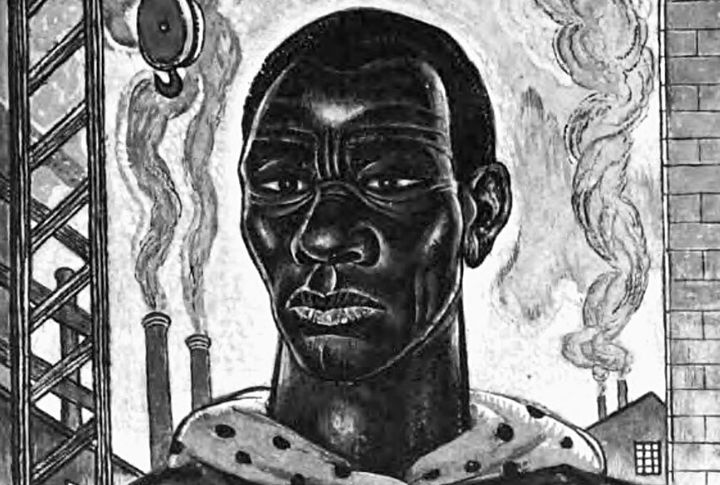

John Henry

Stories tell of a mighty laborer who won the race against a steam drill but died during that effort. Ballads of the late 19th century turned him into a symbol of dignity and resilience in the face of industrialization. Yet historians find no reliable evidence of John Henry.

The Amazons

Ancient Greek writers described the Amazons as fearsome female warriors who lived apart from men and battled alongside or against heroes like Achilles. Archaeology suggests that inspiration may have come from Scythian nomadic women who fought on horseback in battle.

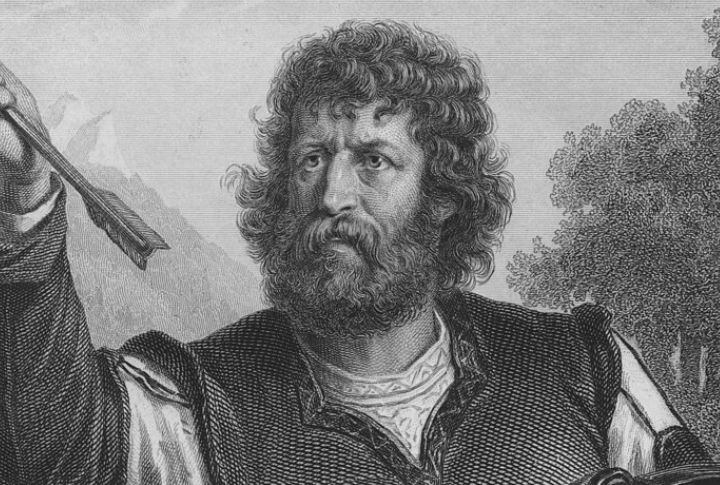

William Tell

Legend has it that William Tell, a Swiss folk hero, resisted oppression by refusing to salute a hat placed atop a pole by a Habsburg authority. He was later forced to shoot an apple placed on his son’s head with a crossbow. The tale first appeared in 15th-century chronicles, but historians find no evidence of Tell’s existence.

Faust

Although Johann Faust lived in 16th-century Germany as a wandering scholar, the legendary figure who sold his soul to the devil is a purely literary creation. Writers like Christopher Marlowe and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe shaped him as an archetype of ambition gone too far, warning against the peril of unchecked desire.

The Children Of Hamelin

The story says a man lured the children of Hamelin after the townspeople refused to pay him. Some think it reflects real events like emigration or disaster. A town record from 1384 mentions that 130 children vanished mysteriously, though the cause was never explained.

Captain Charles Johnson

The “General History of the Pyrates” (1724) shaped nearly all modern images of piracy, from Jolly Rogers to swashbuckling captains. Credited to Captain Charles Johnson, the author’s true identity remains a mystery. Some scholars suspect Daniel Defoe, while others argue the name was a convenient pseudonym.

Ned Ludd

The “Luddite” uprisings of 1811–1816 rallied around a figure named Ned Ludd, supposedly a worker who smashed machines in protest. The name was likely invented to personify resistance against industrialization, allowing real workers to act anonymously under a symbolic leader. Court documents confirm no individual Ludd was ever tried.

The Lady Of The Lake

In the Arthurian legend, the Lady of the Lake is the sorceress who gave King Arthur his sword Excalibur and cared for Lancelot. She appears in many versions of the stories, written by authors like Chretien de Troyes and Thomas Malory. The earliest known references to her date back to 12th-century French romances.

Romulus

Roman tradition claimed Romulus eliminated his brother Remus before establishing the city of Rome in 753 BCE. Ancient writers, such as Livy and Plutarch, preserved the tale, but archaeology provides no evidence of twin founders. The myth likely arose to explain Rome’s drawing on Indo-European twin motifs rather than real historical figures.

Prince Hamlet

The Danish prince immortalized by Shakespeare was loosely inspired by stories in “Gesta Danorum,” written by Saxo Grammaticus in the 12th century. However, no historical record of Hamlet as a real person exists. Shakespeare reworked the medieval legend into a psychological drama, which ensured Hamlet’s place in literature.

The Cynocephali

Medieval travelers’ tales described distant lands populated by Cynocephali, men with dog-like heads. Writers like Marco Polo mentioned them, and even saints’ legends—such as St. Christopher—incorporated the imagery. These myths reflected attempts to explain foreign cultures through monstrous archetypes that lack archaeological evidence.