Danger doesn’t always look obvious—sometimes it’s microscopic. The U.S. has encountered viruses that tested resilience, disrupted lives, and forced a new understanding of health threats. Each of them brought consequences that still linger long after the headlines faded. Read on to discover which viruses have shaped history and why they remain so dangerous.

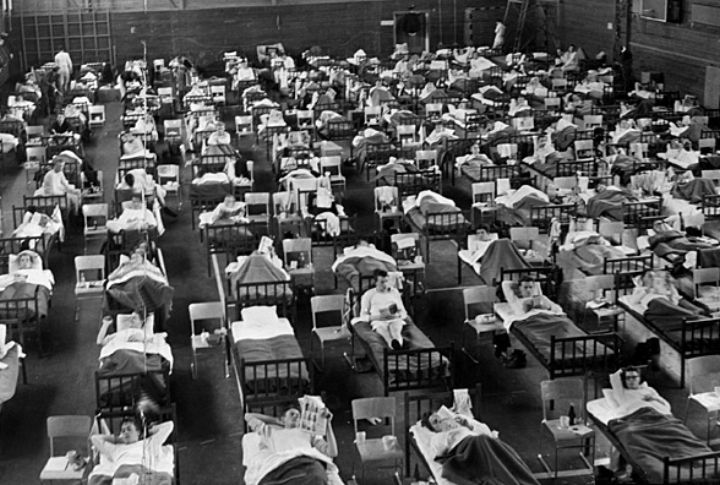

Spanish Flu (H1N1) Pandemic Of 1918

In 1918, soldiers returning from war unknowingly carried a virus. Within months, the Spanish Flu spread across every U.S. state, claiming 675,000 lives. Unlike typical flu strains, it struck young adults hardest. Its exact origins remain debated, yet it became one of the deadliest pandemics in American history.

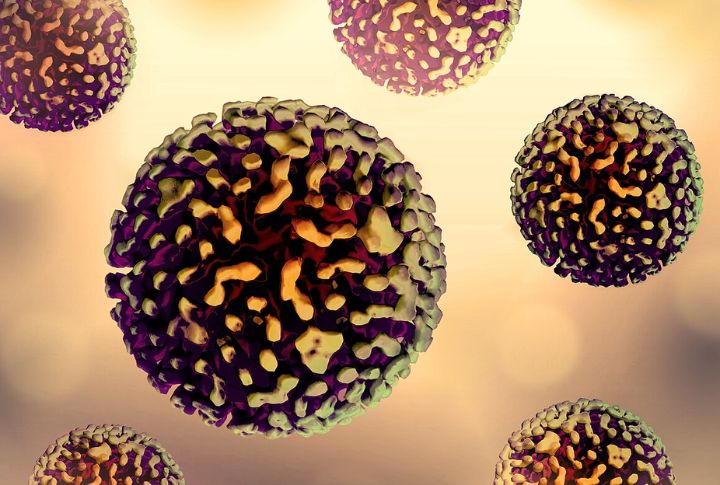

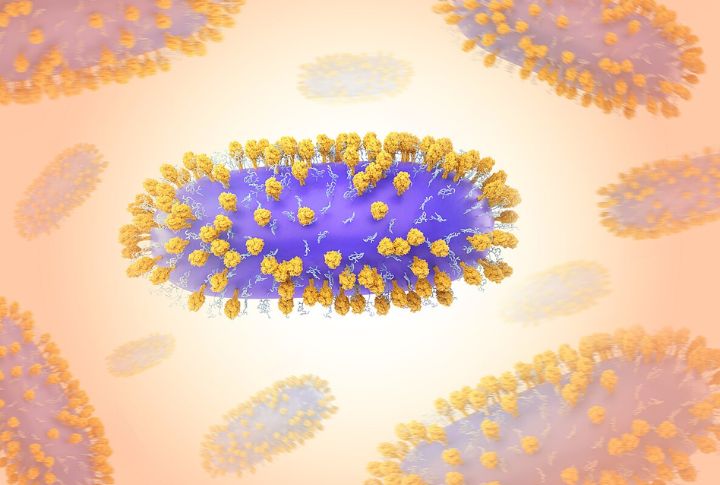

COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) Pandemic

COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, changed American society more than any event since the 1918 flu. First detected in Washington in January 2020, the virus spread rapidly nationwide. Over one million Americans died by 2025. During this crisis, “social distancing” became a household term, and vaccines arrived faster than ever before.

West Nile Virus Outbreaks

Health officials traced the first U.S. appearance of West Nile Virus back to 1999. Birds carried it, mosquitoes spread it, and outbreaks peaked in warmer months. Since then, it has caused over 2,300 deaths. While most cases are mild, it’s dangerous for older adults and immunocompromised individuals.

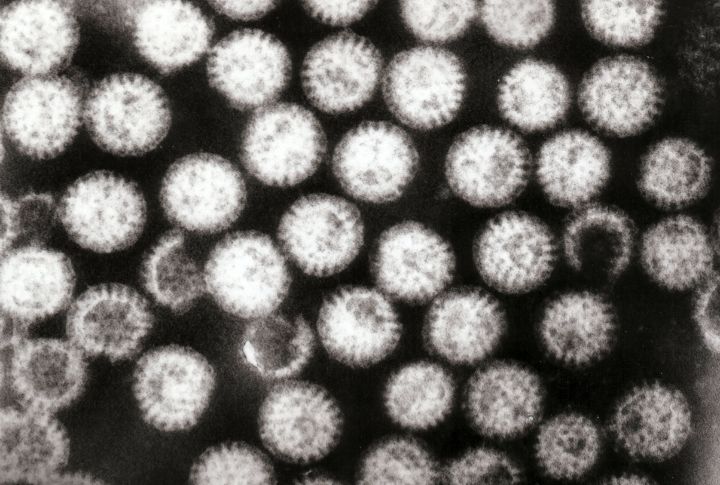

1957 Asian Flu (H2N2) Outbreak

In 1957, a flu came from East Asia and tore through America. About 116,000 people died, and schools were like little flu factories. The wild part? Everyone was focused on Sputnik instead of the outbreak. Thankfully, a vaccine was developed quickly, which helped slow the spread.

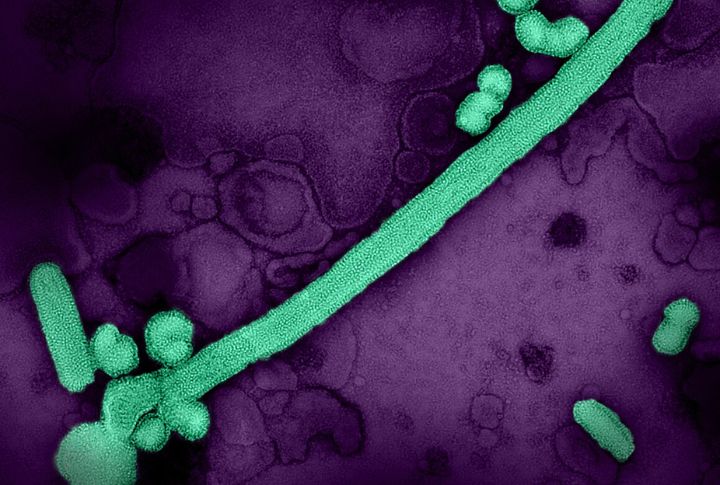

HIV/AIDS Crisis

HIV/AIDS surfaced in the 1980s and has since claimed over 700,000 American lives. Early on, it was called GRID, a label that deepened stigma. And when NBA superstar Magic Johnson revealed in 1991 that he had HIV, it altered public attitudes. Today, with powerful HIV medications, the disease is managed as a chronic illness.

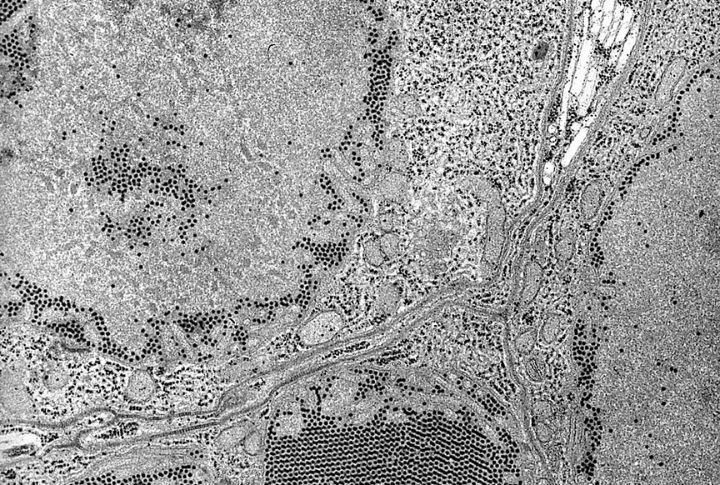

Polio Epidemics (Pre-Vaccine Era)

Back then, polio was every parent’s nightmare. Each year, it struck thousands of kids, leaving many paralyzed and others dead. Some children grew so weak they couldn’t breathe and had to live inside iron lungs. However, the March of Dimes, a charity founded by FDR, funded research, and Dr. Jonas Salk’s unpatented vaccine changed everything.

1968 Hong Kong Flu (H3N2) Pandemic

The flu that started in Hong Kong in 1968 didn’t take long to reach America. With everyone traveling and gathering for the holidays, it spread like wildfire and took about 100,000 human lives. And here’s what’s surprising—it never went away. That same H3N2 virus still resurfaces every flu season.

2009 Swine Flu (H1N1) Pandemic

The Swine Flu circulated fast, with about 60 million Americans getting sick and over 12,000 losing their lives. Unlike most flu seasons, kids and young adults faced the brunt. When vaccines ran short, fear and frustration grew as communities worried about staying safe.

Measles Before Vaccination (Pre-1963)

Before the measles vaccine arrived in 1963, the disease was nearly unavoidable. Almost every child in America caught it. Each year, hundreds of lives were lost and thousands required hospital care. Outbreaks disrupted schools, while health officials launched campaigns urging families to stay alert and take protective steps.

Smallpox In Early America

Smallpox was once every family’s nightmare. During the Revolution, George Washington, commander of the Continental Army and later the first U.S. president, took the unusual step of inoculating his troops. And the real breakthrough came when cowpox was found to provide protection.

Seasonal Influenza (Annual Flu)

Every winter, the flu shows up like an unwelcome guest. This hospitalizes hundreds of thousands and results in the deaths of 12,000 to 52,000 Americans each year. Additionally, Doctors roll out vaccines annually, although their effectiveness shifts as the virus mutates. Surprising part? Today’s flu viruses still carry remnants of the deadly 1918 strain.

Hepatitis C (Chronic Virus)

Hepatitis C is one of those diseases people didn’t talk about much, but it was deadly. Starting in the 1980s, it spread silently, usually through transfusions before blood was screened, and it became the main reason people needed liver transplants. The big change came in the 2010s, when new antivirals actually cured it.

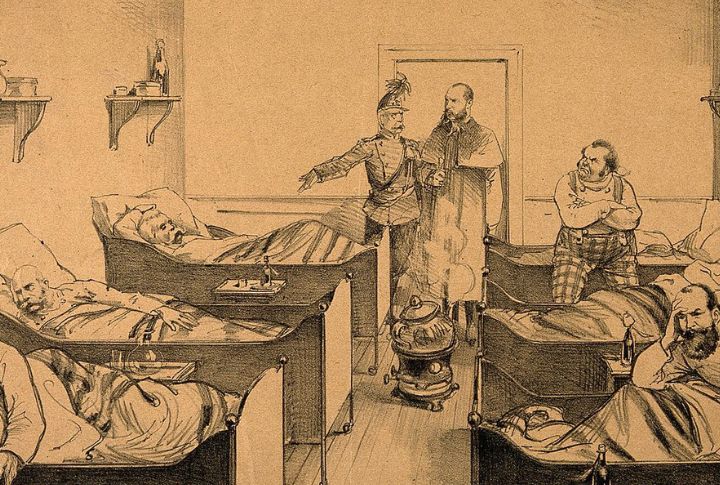

Rabies In 19th-Century America

Imagine 19th-century America, where a dog bite could mean certain death. Rabies claimed thousands of lives, with no cure once symptoms appeared. Also, panic spread during “mad dog” scares in crowded cities, as people feared who might be next. But hope finally arrived after French scientist Louis Pasteur introduced the first rabies vaccine.

Hepatitis B Epidemics

For years, Hepatitis B quietly moved through communities, taking lives without people realizing it. It caused thousands of deaths annually in the U.S., usually by damaging the liver. Healthcare workers were also among the most exposed. That’s why it earned the nickname “silent killer.” Everything changed in 1981, after the first vaccine was introduced.

Rotavirus In Children (Pre-Vaccine Era)

Rotavirus may not be a household name, but before vaccines, it was devastating. Children caught it easily, especially in daycares, and it usually led to hospital stays. In the U.S., thousands of infants ended up hospitalized each year until the vaccine arrived in 2006. In poorer nations, however, it still remains a major threat.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV) & Cancer Deaths

Many people don’t realize just how common HPV is. Almost every adult gets it at some point, often without symptoms. The real danger appears later, when it can turn into cancer. Each year, about 36,000 Americans are diagnosed with HPV-related cancers, and thousands die from cervical, throat, or rectal cancers.

RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus) In Infants

RSV was one of those viruses parents knew to fear. Each winter, it packed hospitals with sick infants and claimed hundreds of young lives. Doctors named it for the cell “fusion” it causes, and it always seemed to spike during flu season. After decades, vaccines arrived in 2023, finally changing the story.

Encephalitis Viruses (St. Louis Encephalitis)

In the 1930s, Missouri faced the first major outbreak of St. Louis encephalitis, which took hundreds of lives. Doctors initially mistook it for meningitis because the symptoms were so similar. Later, they identified mosquitoes spread the virus, making summers frightening. While such large outbreaks never returned, smaller ones continue to appear across the U.S.

Varicella (Chickenpox, Pre-Vaccine Era)

Before the vaccine, chickenpox infected nearly every American child. It was usually mild, but it still caused 100–150 deaths annually, particularly among adults and pregnant women. The virus stayed hidden after infection and could resurface later in life as a painful rash—a lingering reminder of chickenpox’s once-universal presence.

Russian Flu (1889–1890 Pandemic)

In 1889, newspapers were filled with alarming reports about the “grippe,” later called the Russian Flu. It struck U.S. cities hard, leaving tens of thousands dead. What makes it even more intriguing is the mystery that lingers—did influenza truly cause this pandemic, or was it an early coronavirus?