Buried in red ochre and silence, an ancient culture once thrived where Maine’s forests and coastline meet today. Their customs challenge assumptions about early North American societies. Though no written stories remain, traces linger in soil and stone. Through archaeology and oral echoes, this article explores the enduring mystery of a people lost beneath pigment and time.

Graves Awash In Crimson

Along Maine’s coast, archaeologists have discovered ancient graves tinted with red ochre, dating back to around 3,000 to 5,000 BCE. The pigment-covered skeletons were buried with tools like gouges and stone blades. These striking ceremonial burials led to the nickname “Red Paint People,” though their actual identity is still a mystery.

Older Than Most Know

The Red Paint culture predates known Northeast tribes by millennia. Radiocarbon dating places them deep in the Late Archaic period. Their existence predates the arrival of agriculture and pottery in the region, which challenges assumptions about when complex social behavior emerged in North America.

Maritime Specialists Of The Archaic World

Grave finds included toggling harpoons and slate tools, all crafted for life at sea. Archaeological sites like the Turner Farm in Maine reveal that these communities relied on coastal resources throughout the year. Isotope analysis of their bones backs this up, showing a diet rich in marine protein—especially cod and shellfish.

Ochre’s Role Beyond The Dead

Red ochre was not confined to burial sites. It appears in residential areas and is likely used in body paint or rituals. Its symbolic use parallels that of other archaic cultures worldwide, suggesting that it marked important transitions, such as birth or healing, not just death. Its meaning extended far beyond the grave.

Absent Structures, Misread Legacy

No permanent dwellings have been linked to this culture. Archaeological layers hint at seasonal movement between inland and coastal camps. Their temporary structures left little trace and misled early archaeologists to assume cultural simplicity. Yet their mobility reflects adaptation, not the absence of complexity or planning.

Climate May Have Been The Final Push

Around 1000 BCE, rapid sea level rise flooded much of Maine’s ancient coastline. Paleoecological evidence shows submerged campsites and vanished shell middens. These disruptions likely forced migrations inland. Cultural signatures disappear from the archaeological record shortly after. This may indicate that environmental stress ended their coastal way of life.

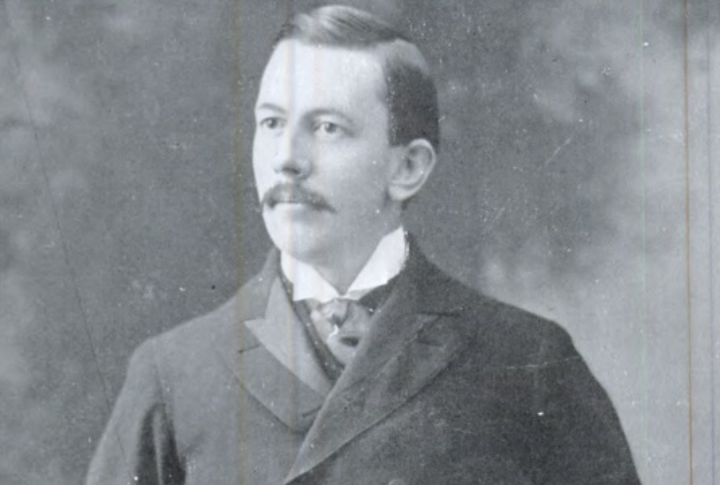

The Disproven Theory Of European Origins

In the early 20th century, archaeologists such as Warren K. Moorehead speculated that the Red Paint People had European ancestry. These claims were based on similarities in burial practices with those of Neolithic Europe. Later research confirmed that their tools and DNA fit within the patterns of North American Archaic cultures. No evidence supports trans-Atlantic contact.

The Problem With Outsider Naming

“Red Paint People” simplifies a complex society into a single burial trait. Like “Anasazi” or “Folsom,” it was coined by outsiders. Their actual name and beliefs remain unknown. Archaeological labels often obscure cultural richness by making it harder to understand ancient people as fully realized societies.

Echoes In Modern Indigenous Memory

Wabanaki oral traditions describe ancient mariners who traveled seasonally and used red pigment in ceremonies. Some scholars see echoes of the Red Paint People in these stories. While archaeological links remain debated, Indigenous knowledge may preserve elements of lifeways that were long thought to be lost to time.

Why They Still Matter

The Red Paint People reflect a society rooted in seafaring and adaptation. Their existence pushes back the timeline of organized culture in New England. Including them in historical narratives restores depth to North America’s past and acknowledges those whose names may never be known.