Native American architecture reveals a deep understanding of the environment, mobility, and sustainable design. Far more than rudimentary shelters, these homes showcased innovative use of natural materials and sophisticated engineering suited to specific climates and cultures. Here are 20 examples that rival modern standards in energy efficiency and adaptability.

Earth Lodges

Earth lodges, built partially underground, used thick layers of soil and grass over a wood frame for insulation. Tribes like the Mandan and Hidatsa designed them to maintain stable interior temperatures year-round. Central fire pits provided heat and cooking, while a smoke hole doubled as ventilation. Some measured 40 feet across and housed multiple families.

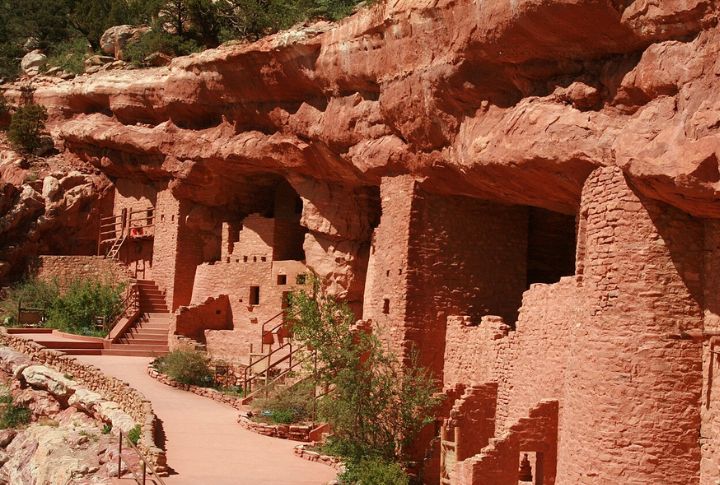

Cliff Dwellings

The Ancestral Puebloans carved homes directly into sandstone cliffs, combining natural rock with adobe and wooden beams. Located in the Four Corners region, these dwellings were positioned for solar warmth and defensive advantage. Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace alone had over 150 rooms and 23 kivas. Many remain structurally intact after over 700 years.

Longhouses

Used by Iroquoian peoples, longhouses stretched to 200 feet and were shared by several families from the same clan. Wooden frames covered with elm bark created durable walls that could flex with wind and snow. The design enabled smoke to exit through the roof vents above each hearth. Also, interior partitions offered privacy while maintaining communal living.

Chickees

Chickees, engineered for swampy environments, were raised on stilts with open sides for airflow. Construction didn’t require nails—just lashing and precision cutting. They were quick to assemble, ideal for a semi-nomadic lifestyle. The Miccosukee and Seminole of Florida built these from cypress logs and palmetto thatch, resisting both flooding and heat.

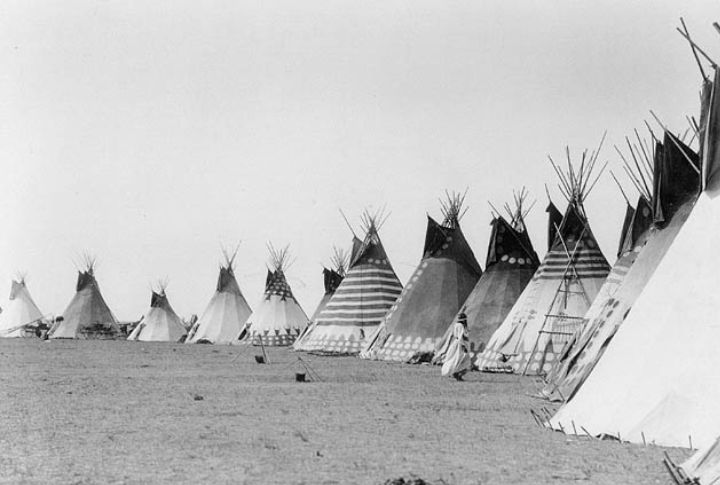

Tipis

Plains tribes built tipis, which were marvels of portable architecture. The structure’s conical shape deflected wind and shed rain, while a smoke hole allowed indoor fires. Poles from lodgepole pine were covered with bison hides stitched for weather resistance. Moreover, a well-placed lining created an insulating air gap, essential for survival in harsh winters.

Adobe Pueblos

The centuries-old Acoma Pueblo, still inhabited today, sits atop a mesa rising 367 feet above the surrounding valley in New Mexico. Southwestern tribes like the Hopi and Zuni crafted multi-story pueblos from adobe—sun-dried mud bricks reinforced with straw. Because they were built for durability in arid climates, their thick walls regulated indoor temperature efficiently.

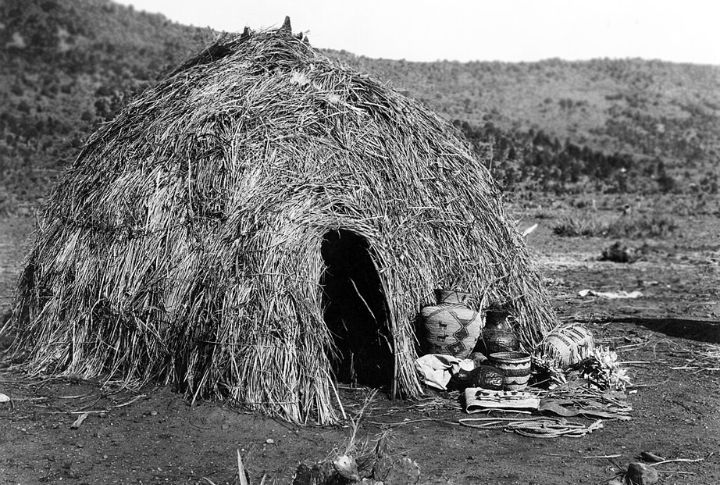

Wickiups

These were constructed by the Great Basin and some Plains tribes. The house featured a dome-shaped frame of saplings covered with brush, bark, or grass mats. Their flexible design allowed for seasonal relocation. Apache wickiups had smoke flaps and doorways oriented for optimal sun and wind exposure. Despite their simplicity, they were remarkably well-ventilated and weather-adaptive.

Plank Houses

In the Pacific Northwest, tribes like the Haida and Tlingit built massive plank houses from cedar logs. Interlocking beams created earthquake-resistant structures with removable roof panels for ventilation. These homes often housed extended families and featured elaborately carved posts. Some reached 60 feet in length and doubled as ceremonial spaces during the winter.

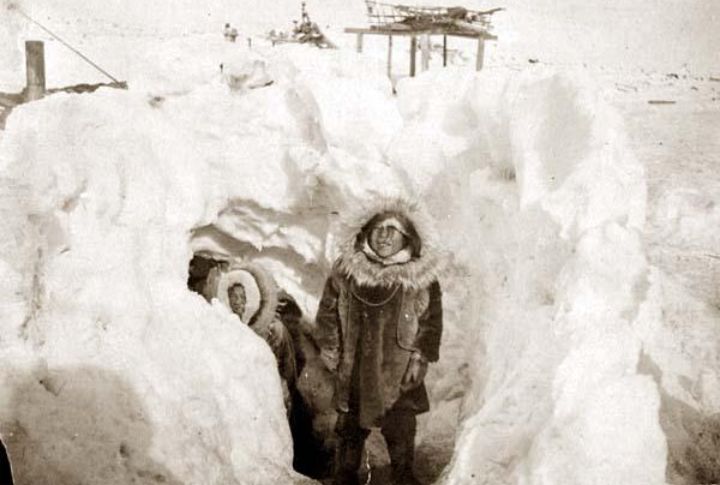

Ice Homes (Qargi)

Inuit communities built communal men’s houses called qargi, often partially subterranean and built with snow or whalebone frames covered in animal skins. The structures served not just as shelter, but also as social and cultural centers. Clever insulation techniques and recessed entryways kept interiors warm even in Arctic blizzards. Tools and weapons were often stored inside.

Grass Houses

The Caddo people of the Southern Plains built tall, beehive-shaped grass houses that could reach 30 feet high. They used a wooden framework covered in tightly packed switchgrass, creating breathable yet insulating walls. A central hearth heated the interior, while a smoke hole above kept the air fresh. The homes were surprisingly resistant to wind and rain.

Subterranean Pit Houses

Native American pit houses were designed for frigid northern climates. They were dug several feet into the ground and topped with timber and earth. Used by Plateau and Arctic tribes, they trapped geothermal warmth while their roof’s central opening was a smoke vent and skylight. Entry was often via a ladder through the roof to conserve wall integrity.

Birchbark Wigwams

In the Northeastern woodlands, Algonquian-speaking tribes built wigwams using flexible saplings bent into a dome and covered in birchbark panels. Birchbark was waterproof, lightweight, and easily repairable. Seasonal variants existed—heavier coverings for winter, lighter for summer. Some versions included bark floors and elevated sleeping platforms to avoid ground moisture in wet forests.

Tule Mat Lodges

These lightweight structures were breathable and quick to rebuild, ideal for a semi-nomadic lifestyle. In winter, double mat layers and interior fires added insulation. Some tule homes were even built directly over shallow water for cooling. Tribes like the Wintun and Ohlone of California crafted them with tule reed mats draped over willow frames.

Hogan

The Navajo hogan featured a circular or octagonal layout with an east-facing door for the morning sun. Traditional versions used logs and packed earth to form thick, insulating walls. A central fire pit and smoke hole were essential for warmth and cooking. Modern hogans still play ceremonial roles and are constructed using the same directional principles.

Rock Shelters

Some groups, like those in the Ozark Plateau, utilized natural rock overhangs and caves as living quarters. Each shelter provided ready-made roofs and temperature stability. Enhancements included stone walls, fire pits, and drainage trenches. Evidence of long-term habitation includes charred hearths and storage pits dating back over 6,000 years in places like Bluff Dweller’s Cave.

Dugout Canoe Shelters

Though primarily transportation tools, these large dugout canoes were occasionally repurposed as temporary shelters by coastal tribes during travel. They were flipped and propped with branches, offering quick cover from rain or wind. Tribes like the Chinook used red cedar canoes, which were rot-resistant and naturally insulated. These dual-purpose designs showed remarkable spatial efficiency.

Snow Houses (Igloos)

Built by Inuit peoples, igloos were more than snow huts: they were precise, engineered structures. Blocks of compacted snow formed a spiral dome that distributed weight evenly, preventing collapse. Inside, temperatures could stay around 60°F despite subzero conditions outside. A raised sleeping platform kept bodies above cold air pockets.

Kiva Structures

Though used primarily for ceremonial purposes, kivas were subterranean round rooms built by Ancestral Puebloans. Despite their religious function, their architectural sophistication stands out: ventilation shafts, deflector stones, and sipapus (symbolic openings) all served specific purposes. The largest, like the Great Kiva at Chaco Canyon, featured massive wooden roofs supported by stone masonry.

Sod Houses

In the subarctic and prairie regions, sod houses, used by tribes like the Inuit and Cree, offered thick insulation from stacked earth and turf. Sod bricks were often laid over log or driftwood frames, and walls could reach two feet thick, ideal for brutal winters. Each home blended with the terrain and retained interior heat exceptionally well.

Brush Shelters

Bush shelters were crafted from readily available branches, leaves, and grasses and often used as seasonal or temporary dwellings. Though rudimentary, they were optimized for shade, ventilation, and camouflage. Some incorporated woven panels for windbreaking and drainage during sudden weather shifts. Tribes like the Chumash and Yaqui built them near hunting grounds or water sources.