You’ve probably heard the name and maybe seen the statue. But the full picture of Richard the Lionheart stays hidden behind titles and battle tales. His time in England was brief; his choices were shaped by loyalty elsewhere. And his legacy? More complicated than it seems. These 20 facts reveal the life behind the legend.

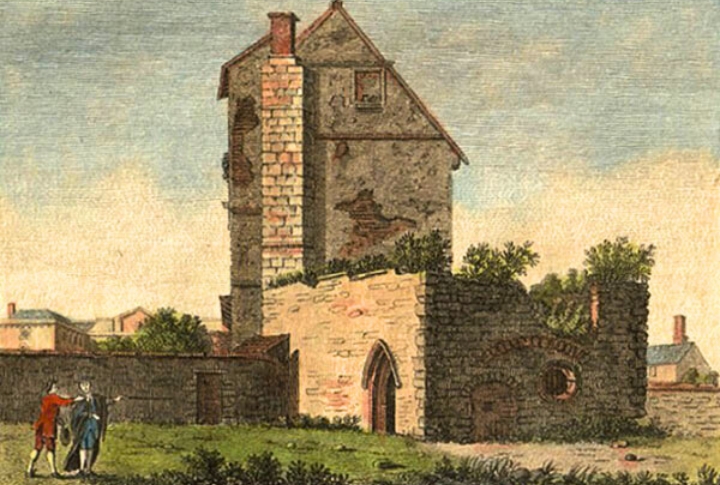

Born In Oxford But Rarely Set Foot In England

Beaumont Palace in Oxford marked Richard’s beginning, but England hardly saw him after. His adult life unfolded in Aquitaine and Normandy, where he ruled and campaigned. French and Occitan were his languages of choice. England was mostly a place to collect funds, not a kingdom he personally invested in.

Made Duke Of Aquitaine At Just 14

The title came early, and so did the responsibilities. At just 14, Richard became Duke of Aquitaine and Poitiers, lands inherited through his mother, Eleanor. To keep control, he launched ruthless campaigns against defiant nobles. He remained loyal to these territories long after becoming king of England.

Earned The Name ‘Lionheart’ On The Battlefield

This name wasn’t symbolic—it was earned in 1191 as Richard took Acre and later fought at Arsuf. His leadership in the Crusade drew praise from chroniclers across Europe. Courage under pressure, especially during open battle, became a lasting part of how his story was recorded and retold.

He Twice Rebelled Against His Father, Henry II

Richard joined his brothers in a revolt against their father in 1173–74, then clashed with him again in the 1180s over succession rights. These uprisings destabilized the Angevin Empire and deepened family divisions. Their final conflict ended only with Henry’s death, shortly before Richard became king.

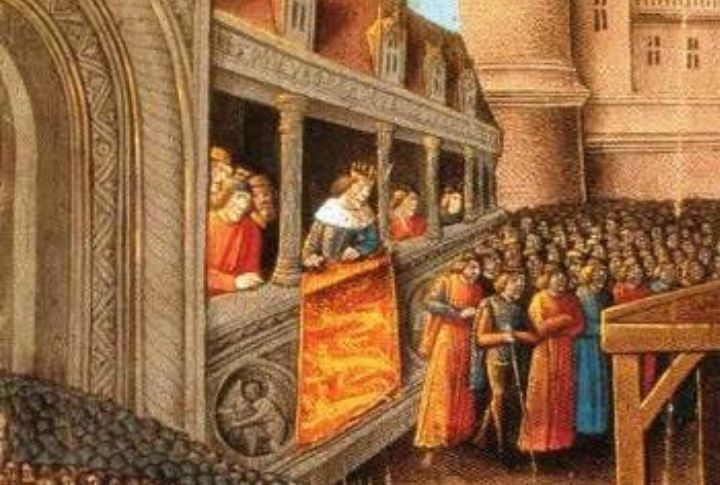

Crowned King In 1189 Amid A Blood Moon

On September 3, 1189, Richard was crowned at Westminster, but the event was far from smooth. A bat circled the king’s head, bells rang without cause, and tensions ran high. Jews were barred from attending. Within hours, anti-Jewish violence broke out and quickly escalated across multiple English cities.

Left For The Crusade Almost Immediately

Not long after taking the crown, Richard departed for the Holy Land in December 1189. Preparing for war took priority over ruling at home. To fund the Crusade, he sold royal titles and land. At one point, he even joked he’d sell London if someone named a price.

Richard’s Campaign Trail Ran Through Messina And Cyprus

In 1190, violence erupted in Messina after tensions rose between locals and Richard’s men. He took the city by force. The following year, he invaded Cyprus, removed its ruler, and sold the island to the Templars. The operation freed his sister Joan and strengthened his military position.

Acre’s Siege Ended With A Controversial Mass Execution

Negotiations collapsed after Acre’s surrender in 1191, and Richard acted decisively. He ordered the execution of approximately 2,700 captured defenders, an event later known as the Massacre of Ayyadieh. The move sparked outrage across Europe and angered Saladin. While some called it strategic, others viewed it as cruelty that stained his record for generations.

He Refused The Crown Of Jerusalem In 1192

After the passing of King Guy and rising tension among Crusader factions, Richard was offered the crown of Jerusalem. He declined and backed Conrad of Montferrat instead, aiming to avoid further division. The decision preserved political unity among Crusaders but kept him from claiming a symbolic victory.

He Reached Jerusalem’s Outskirts But Refused To Attack

During the Third Crusade in 1192, Richard advanced to within 12 miles of Jerusalem. He decided not to launch an assault, fearing they couldn’t hold the city afterward. Instead, he withdrew to the coast. The choice preserved his forces but disappointed many of his Crusader allies.

He Was Captured In Austria After The Third Crusade

After the end of the Third Crusade, Richard’s ship was wrecked in the Adriatic Sea. Traveling overland in disguise, he was arrested near Vienna by Duke Leopold V of Austria. His identity was revealed by his royal ring and accent. Despite Church protections, Leopold publicized the arrest.

He Composed Poetry While Held In Captivity

During his imprisonment in Germany, Richard wrote a poem titled Ja nus hons pris in Occitan. It expressed his frustration at being abandoned by allies. The song circulated widely and survives in multiple versions. As a king and troubadour, he used verse to shape his public image.

His Ransom Equaled Two To Three Years Of Royal Income

Emperor Henry VI demanded 150,000 marks for Richard’s release—more than double England’s annual revenue. The money was raised in various ways, which included taxing the clergy and melting royal plates. Leopold and the emperor openly announced Richard’s location to speed up negotiations and ensure payment.

Eleanor Of Aquitaine Led The Ransom Effort Herself

To secure Richard’s release, his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, organized the collection of the 150,000 marks. She traveled across England and Aquitaine, rallying loyalty and extracting funds. Her leadership prevented the Angevin Empire from fracturing during his absence. She personally delivered the final ransom payment to Germany.

He Pardoned John Despite His Alliance With France

While Lionheart was imprisoned, his brother John allied with Philip II of France and attempted to seize the throne. After Richard’s release in 1194, he chose to pardon John and name him heir. The decision was strategic, meant to stabilize the dynasty despite John’s betrayal.

A Crossbow Bolt Ended His Life At Chalus

In 1199, Richard besieged the castle of Chalus for rumored treasure. During the attack, he was struck by a crossbow bolt and later died from infection at the age of 41. Before dying, he reportedly forgave the young archer who had wounded him, though the man was later executed.

He Died Without Leaving A Legitimate Heir

Richard married Berengaria of Navarre, but they had no children. His only known son, Philip of Cognac, was illegitimate and excluded from succession. After Richard’s death, a power struggle followed between his brother John and his nephew Arthur of Brittany. The conflict weakened the Angevin hold on power.

His Body Was Divided Between Three Burial Sites

After he died in 1199, Richard’s heart was buried in Rouen Cathedral, his body in Fontevraud Abbey, and his entrails at Chalus. The division reflected his ties to Normandy, Anjou, and the place of his death. In 2013, analysis of his heart revealed traces of frankincense and mercury.

He Introduced England’s Three Lions Emblem

Lionheart’s royal seal featured three lions passant guardant, an emblem that became the royal arms of England. The symbol still appears on national teams and government insignia. It linked monarchy to battlefield valor and has remained one of the most recognizable heraldic images in English history.

His Legend Was Reinvented Centuries After His Passing

In the 19th century, British writers and politicians revived Richard’s image as the ideal Christian king. A statue honoring him was placed outside Parliament in 1851. Schoolbooks and public art reimagined him as a national hero, though modern historians view his rule with far more caution.