Ever say something weird and wonder, “Wait—why do I even know that phrase?” Turns out, a lot of our everyday sayings come with strange, dusty backstories. War wounds, graveyard bells, powdered wigs—you’re about to find out how wildly literal some expressions used to be.

“Bite The Bullet”

Before anesthesia, wounded soldiers bit down on bullets during surgery to endure extreme pain. Some actual bullet fragments have even been discovered in war zones. The phrase first appeared in Rudyard Kipling’s 1891 novel, capturing the harsh realities of combat medicine.

“Mad As A Hatter”

Hat-makers in the 18th and 19th centuries used mercury nitrate, which caused tremors and hallucinations. This condition became known as “hatter’s shakes.” Lewis Carroll’s famous Mad Hatter character was directly inspired by these mercury-poisoned workers and their bizarre, erratic behavior.

“Cost An Arm and A Leg”

In the 1700s, portraits were priced based on the number of limbs depicted. Full-body paintings with arms and legs were significantly pricier. To save money, many clients opted for just head-and-shoulder shots. The phrase gained popularity in post-WWII American slang.

“Let The Cat Out Of The Bag”

At old European markets, dishonest sellers replaced valuable pigs with cheap cats in closed bags. Once opened, the trick was revealed—hence the phrase. The saying stuck after 18th-century buyers repeatedly fell for the scam, especially when buying without checking.

“Kick The Bucket”

Animals were once hung from a beam, also called a bucket, before slaughter. As they died, they’d kick against it, inspiring the phrase. Used as early as 1785, it became slang for dying and later spread through both literature and everyday speech.

“Saved By The Bell”

In the 18th century, people feared being buried alive. So, some coffins included a bell connected to the buried person’s hand. If they moved, the bell rang. This gave rise to the saying and likely the term “graveyard shift” for night watch duty.

“Close But No Cigar”

In 19th-century carnivals, winners earned cigars, not plush toys. When players came close but lost, workers shouted, “Close, but no cigar!” Games were often rigged to ensure a predetermined outcome. The phrase later became popular in everyday language for near misses or efforts.

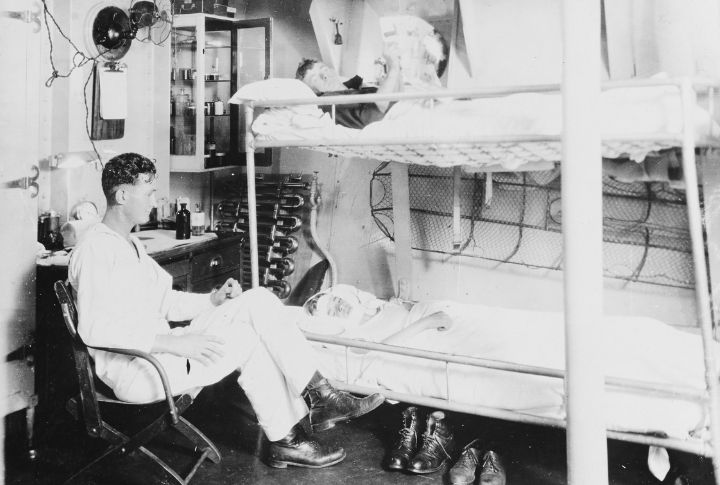

“Under The Weather”

Sailors who felt ill during storms were sent below deck to recover—literally “under the weather.” The phrase, recorded in the 1800s, reflected a sailor’s poor condition during rough seas. It later expanded to describe general illness or being unwell on land.

“Break The Ice”

In cold waters, icebreaker ships were used to clear trade routes and allow communication between them. The term became a metaphor for easing tension. Shakespeare used a version of it in “The Taming of the Shrew”, showing its early role in social interaction.

“Turn A Blind Eye”

Admiral Nelson ignored orders by lifting his telescope to the blind side, as he was blind in one eye, and claiming he saw nothing. He went on to win the battle. The phrase later symbolized intentional ignorance of rules or inconvenient facts.

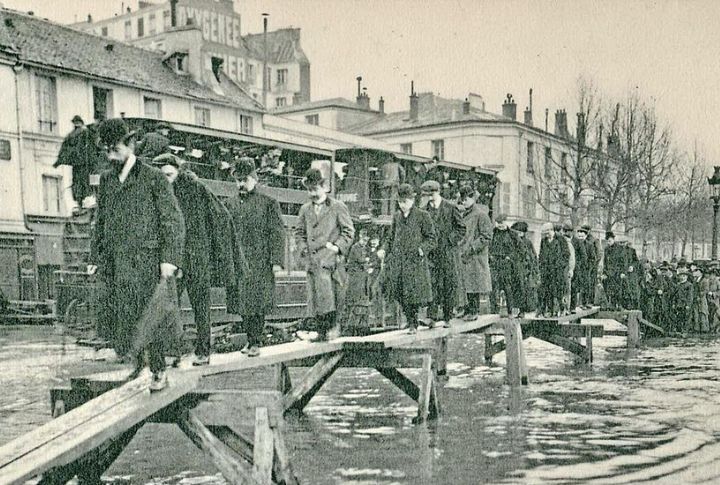

“Raining Cats And Dogs”

In 17th-century Europe, poor drainage systems sometimes flushed out animal corpses during heavy rain. The shocking frequency of this scene gave the phrase staying power. Jonathan Swift used it in a 1710 satire. Others later linked it to Norse mythology and animal spirits.

“Caught Red-Handed”

Scottish law once punished hunters found with fresh animal blood on their hands. The term “red-handed” referred to undeniable proof of wrongdoing. It dates to the 1400s and later spread to describe anyone caught in the act—no questions, no excuses.

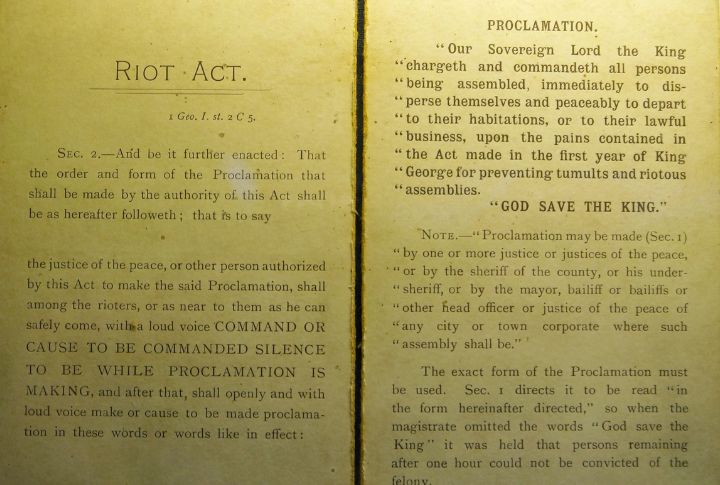

“Read The Riot Act”

In old England, reading the Riot Act wasn’t just a figure of speech. Officials had to recite it—out loud—to disperse unruly crowds. Anyone lingering an hour later could be arrested or met with force. The law remained active until 1973, giving literal meaning to the warning.

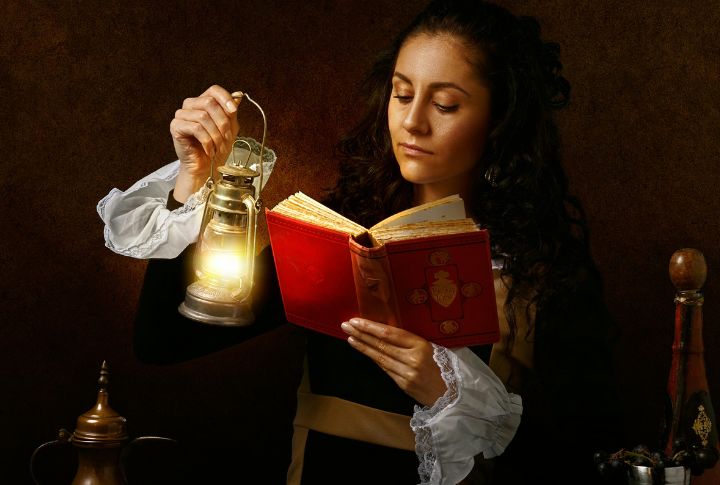

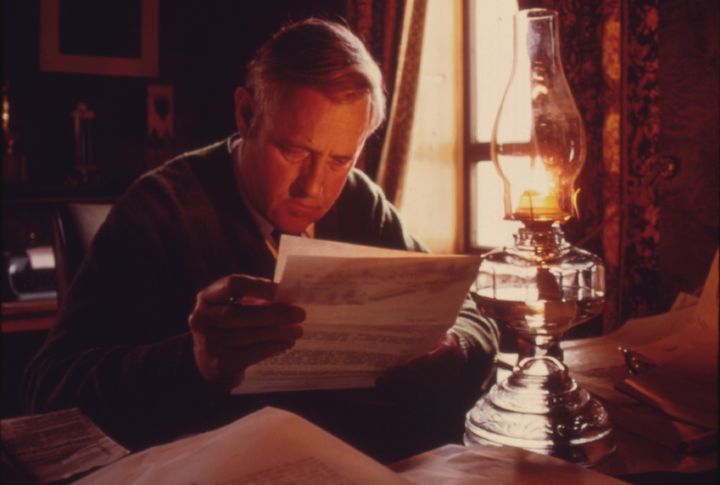

“Burning The Midnight Oil”

Before modern lighting, oil lamps provided illumination for late-night studying or writing. Only the wealthy could afford long burns, making the effort notable. The phrase appears in 17th-century poetry and came to symbolize hard work happening while most people were already asleep.

“Toe The Line”

British sailors stood at deck seams during inspections, literally aligning their toes to the line. The expression symbolized discipline and exact conformity. It’s often miswritten as “tow the line,” though Parliament helped standardize the correct version in political settings.

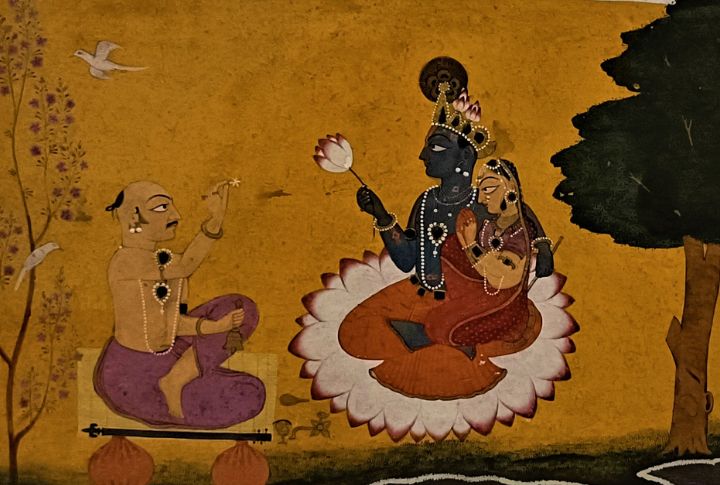

“Butter Someone Up”

Ancient Indian worshippers offered balls of butter to idols, hoping for blessings. Over time, the act became symbolic of seeking favor. The phrase entered English during the 1700s and is now a casual way to describe flattery with a hidden intent.

“Go Cold Turkey”

Sudden drug withdrawal often causes goosebumps—skin that resembles raw turkey. The phrase appeared in The Daily Express around 1921 and referred to quitting without tapering. “Cold turkey treatment” was considered abrupt but effective, especially among recovering addicts needing fast, clear-cut detox.

“Pull Out All The Stops”

Pipe organs have adjustable stops that control airflow and sound. Removing all of them releases full volume. Victorian preachers often ended sermons this way. The phrase came to represent maximum effort, doing everything possible without holding anything back musically or otherwise.

“The Whole Nine Yards”

First used in 1855 as a joke about an oversized shirt, this phrase later took on serious meaning. WWII pilots used the full 27-foot ammo belt in combat, giving the “whole nine yards.” Surprisingly, it also appeared in football, cement mixing, and sewing contexts.

“No Spring Chicken”

In colonial New England, spring-hatched chickens sold for higher prices. Older birds were cheaper and harder to sell. Buyers caught on, and “no spring chicken” became slang for someone no longer youthful, especially when trying to pass as younger than they were.