Imagine a world where even the smallest detail of your behavior could make or break your reputation. For centuries, this was the reality for many, as etiquette not only dictated social status but, in some cases, determined survival itself. What seems ordinary today once held tremendous significance. So, let’s take a look at ten peculiar customs that reveal just how strange and sometimes downright exhausting “good manners” could truly be.

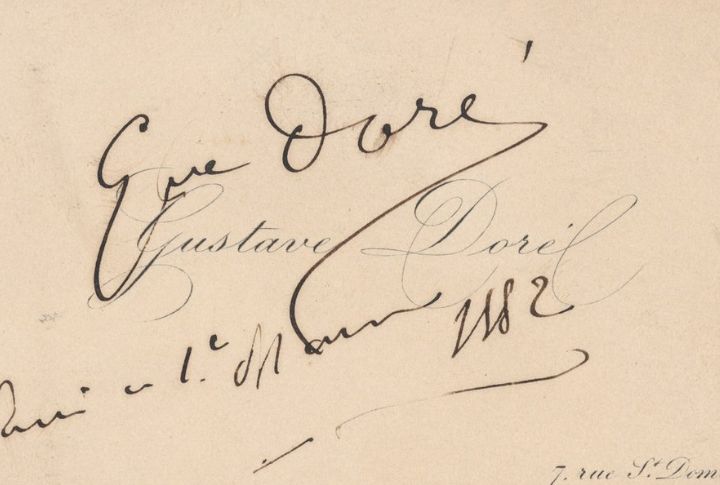

Calling Cards Ruled Social Visits

The calling card system was preferred among the middle and upper classes to maintain decorum and hierarchy. Visitors introduced themselves with engraved calling cards, often embossed with family crests. Servants would deliver the cards on trays, and only then would the hosts decide whether to receive their guests.

“At Home” Days Shaped Hospitality

Cards also announced when visits were allowed. Many women went a step further by scheduling “At Home” days and printing precise hours on their cards. Drop by at the wrong time, and you might risk offense. These carefully planned schedules turned social visits into well-orchestrated performances.

Poetry As Social Etiquette In Heian Japan

At Japan’s Heian court, composing waka poetry was a daily social obligation. Courtiers exchanged verses in person, through letters, or even as part of formal competitions called uta-awase, where skill and wit were judged. The subtlety of a poem could signal high social standing, while a poorly crafted verse might brand a courtier as uncultured or careless.

Mourning Fashion Lasted For Years

After Prince Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria adopted black mourning attire for the rest of her life. Etiquette guides instructed widows to wear dull black for two years, followed by gray or lilac. Clothing symbolized bereavement publicly and turned grief into a codified visual performance.

Fans Spoke A Secret Language

In the 19th century, folding fans served as coded tools of communication, especially for women in high society. The “language of the fan” included signals like hiding the eyes to indicate interest or snapping shut to end the conversation. Mastery meant navigating romance and etiquette simultaneously.

Crossed Legs Marked Disrespect

Edwardian etiquette guides, like Mrs. Humphry’s “Manners for Men” (1897), advised men against crossing their legs in formal settings. Doing so was seen as lazy or insolent, especially in the presence of elders or women. Proper posture meant sitting with a straight back and feet planted firmly on the floor—a subtle signal of discipline and social refinement.

Ground-Kissing Before the Sultan

Ottoman court ceremonies required absolute submission. Visitors performed the “temenna,” a deep bow that could involve touching or even kissing the ground before addressing the Sultan. European diplomats in the 16th and 17th centuries recorded this ritual as mandatory, and failing to follow it could carry serious political consequences.

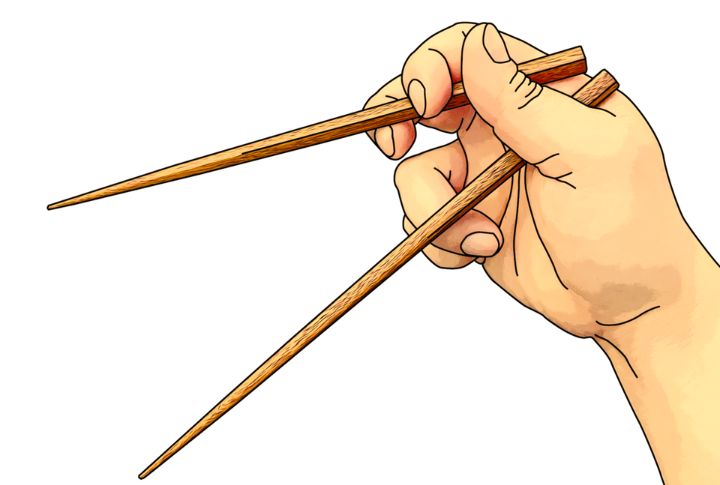

Chopstick Taboos In Imperial China

Chinese dining etiquette forbade sticking chopsticks upright in rice, a gesture resembling incense offerings for the dead. Pointing chopsticks directly at someone was also considered taboo, interpreted as a sign of disrespect. These rules appear in Confucian-influenced ritual texts and show how table manners symbolized harmony and cultural morality at meals.

Gloves Dictated Public Behavior

Victorians took their gloves seriously, and for good reason. Whether you were shaking hands or meeting someone for the first time, gloves stayed on. But timing mattered: removing them too quickly seemed improper, while letting them get worn suggested neglect. And it wasn’t just about keeping them clean—color and style all spoke volumes about who you were.

Formal Bows To Royals In Renaissance Courts

Courtly Europe demanded mathematical precision in greetings. Manuals detailed degrees of bowing: deep bends for monarchs, lighter nods for nobles, restrained gestures for peers. Etiquette schools drilled movements into young courtiers. A misplaced angle could ruin advancement.