In medieval Europe, power derived from land, and land came with strings attached. This was feudalism: a layered, loyalty-based world where rights weren’t equal and freedom wasn’t free. But the world changed, and so did its people. Let’s explore the long decline of this once-dominant social system.

Feudalism Was Never Built To Last

After Charlemagne’s empire collapsed, Western Europe fragmented into small defensive territories. Feudalism emerged from this chaos, built on land exchanged for loyalty and service. With no legal framework or central rule, it depended on fragile personal ties that fractured easily under social or political pressure.

The Black Death Broke The Labor Chain

Between 1347 and 1351, the bubonic plague wiped out at least one-third of Europe’s population. Serfdom collapsed in many regions as labor shortages gave peasants the leverage they needed. Lords were forced to offer wages instead of demanding unpaid labor. Entire manorial economies broke down under this demographic shock.

Runaway Serfs Found Refuge In Growing Towns

Towns across Europe gained charters that granted them legal independence. In England and Germany, a runaway serf who lived in a town for a year and a day became free. Trade and wage labor made urban life more attractive than manorial dependence. The cities offered escape and dignity.

Cash Rent Dismantled Labor Obligations

By the late 1200s, many lords shifted from demanding physical labor to accepting fixed cash rents. The growth of regional trade and coin circulation made this possible. In England, the 1351 Statute of Labourers tried to freeze wages but failed, which shows how feudal obligations no longer matched economic realities.

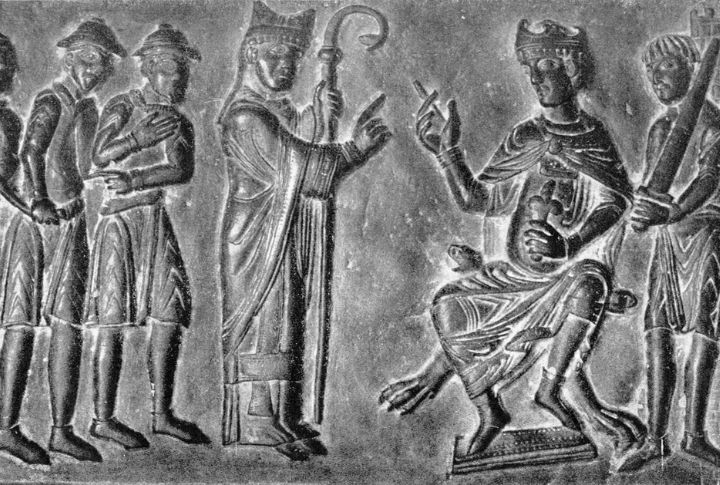

Centralized Monarchies Cut Out The Nobles

As monarchs like Edward I and Philip IV expanded royal authority, they built national courts and tax systems. They no longer needed feudal lords to raise armies. Vassal-based levies gave way to professional soldiers. Feudal intermediaries faded as kings governed directly by weakening the decentralized order on which feudalism depended.

Uprisings Shook The Foundations Of Feudal Control

In 1381, England’s Peasants’ Revolt saw tens of thousands march on London in protest of taxes and feudal injustice. Earlier revolts, like the Jacquerie in France (1358), erupted from similar unrest. Though suppressed, these uprisings revealed a widespread rejection of inherited servitude across medieval Europe.

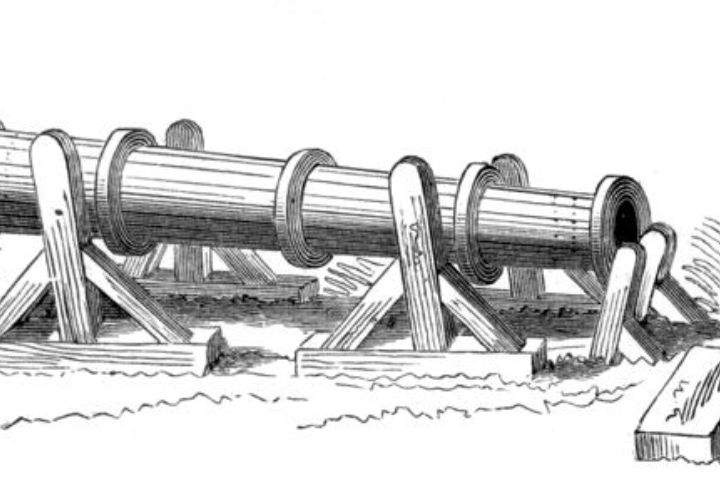

New Weapons Made Feudal Armies Obsolete

Gunpowder weapons, used decisively by the Ottomans in 1453, changed the nature of combat. Armored vassals became liabilities on the battlefield. At Crecy in 1346, English longbowmen crushed French knights by undermining cavalry tactics. As a result, monarchs began investing in professional infantry over feudal levies.

Legal Reforms Weakened The Lords’ Grip

The Quia Emptores statute of 1290 ended subinfeudation in England, which simplified landholding and limited noble power. In Spain, Catalonia’s remensa peasants gained legal paths to freedom. Across Europe, charters and royal courts empowered peasants to challenge obligations by replacing custom-bound systems with negotiated legal contracts.

Nobles Turned Their Estates Into Businesses

By the 1400s, nobles increasingly leased their lands for fixed rents rather than enforcing labor services. French metayers and English copyholders farmed under terms shaped by market logic. Many lords moved to cities, where they moved from acting as rulers to landlords, more interested in profit than feudal governance.

The Crusades Undermined Feudal Lords

The Crusades, launched in the late 11th century, drew many nobles into costly wars far from home. To finance these campaigns, lords often sold land or granted rights to towns. This weakened their local authority and shifted power to merchants and urban institutions, gradually undermining the manorial system they once controlled.