You know that mini heart attack when your snack slips out of your hand and lands on the floor? And instantly you’re like, “Quick, five seconds!” It is the universal rule of not wasting food. But here’s where it gets funny: scientists couldn’t resist checking if it actually works. They ran real experiments, and the results were not in our favor. It turns out that the truth behind this so-called rule is far messier and a lot more fascinating than we thought. Let’s dig into what really happens when your food hits the floor.

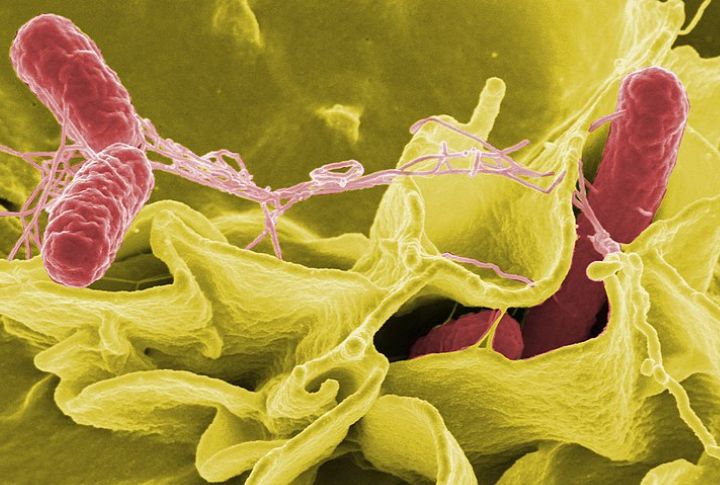

Bacteria Type Matters

Not all bacteria transfer equally. Salmonella Typhimurium can move over 99% of its cells to food within five seconds on tile but under 0.5% on carpet. E. coli O157:H7 spreads up to 8% depending on moisture. So the next time something drops, remember, it’s not just where it lands, but who’s waiting there.

Surface Type Importance

Not all surfaces follow the same rules when food takes a tumble. Bacteria multiply on smooth terrain, so tile and steel give them an easy path to spread. Wood, however, is unpredictable—it might soak up microbes or just pass them along. Then there’s carpet, the surprising hero. Its tangled fibers trap more germs than they share, so your fallen bite ends up with fewer unwelcome hitchhikers.

Clean Surfaces Aren’t Safe

We trust what our eyes see. A polished floor or a spotless surface feels safe. Scientists once thought so too, until their lab tests pushed them into the messy world beyond microscopes. Cafeterias, lecture halls, even places that gleamed under fluorescent light, turned out to harbor hidden life. Clean, it seems, is often just an illusion.

Food Moisture Content

You might assume all candy behaves the same way when dropped, but here’s the twist: while sticky sweets readily collect bacteria, their gummy cousins show remarkable resistance. It’s all about moisture – from relatively safe dry snacks to bologna’s concerning levels, right up to watermelon’s status as the ultimate bacterial playground.

Surface Infectious Duration

Bacteria don’t disappear once a surface dries. Salmonella can survive up to 28 days, waiting to transfer to any food that touches it. What looks like an old mark might actually hide living germs capable of spreading illness long after the mess seems gone.

Environmental Humidity

Ever notice how some days the air feels heavy and sticky, while others are dry and crisp? That same difference plays a big role when food hits the floor. In humid air, germs can linger longer on surfaces, which provides them more chances to hitch a ride onto your snack. When the air is dry, they fade faster, so the risk of a quick transfer drops.

Temperature Of The Surface

Temperature plays a sneaky role in germ transfer. Warmer surfaces—like countertops exposed to sunlight—help bacteria multiply and spread faster. Cold floors or metal surfaces slow their activity, but don’t stop it. Even brief contact with a warm environment can give microbes the boost they need to thrive on your food.

No Safety Standard

You could scour every food safety manual from cover to cover, but you won’t find a single mention of the five-second rule. Not tucked away in a footnote, not hidden in the fine print. Germs couldn’t care less about your reaction time; they cling to food the instant it hits the floor. Sure, it is a comforting little myth we have all leaned on, but science makes it clear: no food is ever “too fast to get filthy.”

Microscopic Matchmaking

It’s almost like some foods and germs were meant to meet. Anything juicy or sweet that contains protein is basically an open invitation for bacteria. Those little guys love a good meal, and the richer the snack, the faster they show up. Scientists found that microbes actually move quickly to foods that give them the nutrients they crave. The worst kind of chemistry—instant attraction, terrible consequences.

Outdoor Vs. Indoor Surfaces

Scientists have measured how bacteria spread indoors, but outdoor surfaces remain largely uncharted territory. Soil, benches, and pavements host unpredictable mixes of microbes that make indoor bacteria look tame by comparison. And when food hits the ground outside, forget the five-second rule—it’s never safe to eat.