Science is rewriting how the first people reached the Americas. Archaeologists and geneticists now reveal that our ancestors didn’t just survive the Ice Age; they conquered it by sea, journeying along the coasts of both North and South America. Scroll through to see how modern evidence is challenging old theories and revealing a migration far more daring than we ever imagined.

Kelp Highway Coastal Migration

Along the Pacific Rim—from Siberia’s coast down through Alaska and the Pacific Northwest—ancient voyagers paddled through vast kelp forests between 17,000 and 15,000 years ago. These underwater jungles offered food and shelter. Following this “kelp highway,” early migrants journeyed south into the Americas.

Submerged Continental Shelf Routes

Those Ice Age routes were humanity’s first superhighways. Then came a cataclysm—the Bolling-Allerod warming—raising seas faster than civilizations could blink. The evidence sank with it. Now, underwater explorers search for the ghost roads where our ancestors once walked.

Early Shell-Midden Coastal Camps

At sites in southern Chile and Argentina near the tip of South America, large ancient shell middens (pileups of shells and food remains) indicate people were exploiting coastal marine resources by at least 14,500 years ago — pushing human arrival in the Americas further back than previously thought.

Channel Islands Archaeological Sites

Just off California’s coast lie the Channel Islands that were never connected to the mainland. Yet, people lived there over 13,000 years ago. That means they arrived by boat. Artifacts found on these islands prove early Americans were skilled seafarers, which challenges the old belief.

Ancient Obsidian Trade Networks

Obsidian, also known as volcanic glass, traveled far, and so did the people who traded it. From Alaska to California, tools made of distant stone reveal early networks of connection. Some exchanges were overland, others possibly coastal. These glossy black relics whisper of prehistoric commerce long before the word “trade” was ever spoken.

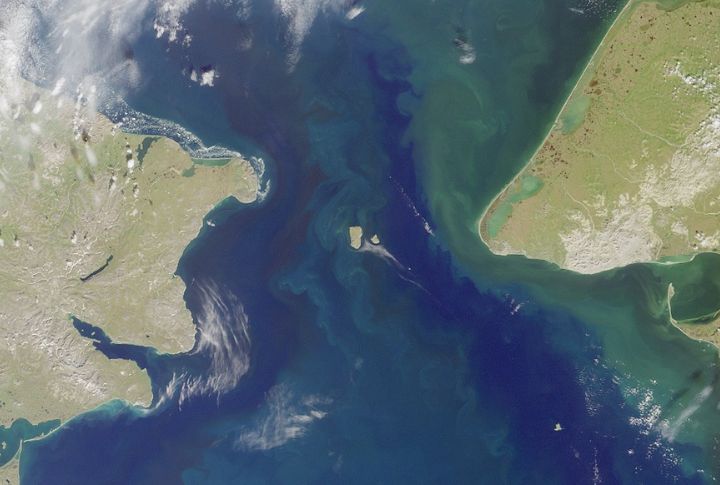

Coastal Beringia Settlement Pattern

Long before borders, Coastal Beringia was home. Stretching between Asia and America, it offered refuge during the Ice Age’s worst years. People lived there for millennia, waiting for the ice to recede. Genetic traces still tell their story of a frozen bridge that became humanity’s great crossing.

Monte Verde Coastal Settlement, Chile

Step into Chile’s Monte Verde, and you step into a 14,800-year-old mystery. This settlement predates the Clovis people, which rewrites how we think humans reached the Americas. The evidence of coastal foods and wooden structures reveals adaptability and innovation. Monte Verde is a story of survival redefined.

DNA Evidence Of Coastal Siberian Origins

Modern genetics now maps humanity’s oldest journeys. DNA from ancient Siberians and East Asians came together 20,000 years ago, pointing toward a coastal migration into the Americas. These were deliberate travelers. Every gene tells a chapter of how the first Americans followed the shorelines of their ancestors.

Stone Tool Technology From Coastal Caves

The story of America’s first toolmakers may not begin on the plains at all. In Oregon’s coastal caves, archaeologists discovered western stemmed points—stone tools predating the famous Clovis spear points by nearly 1,000 years. Their refined craftsmanship and marine setting suggest an early coastal migration, proving innovation reached the shores long before Clovis hunters roamed inland.

Coastal Migration Timing Models

Paleoclimate evidence reveals two ideal migration windows along the Pacific coast—between 24,500–22,000 and between 16,400–14,800 years ago. During these rare intervals, calmer seas, exposed shorelines, and weak northward currents made travel southward not just possible but efficient. Climate didn’t simply permit migration; it actively guided humanity’s earliest explorers.