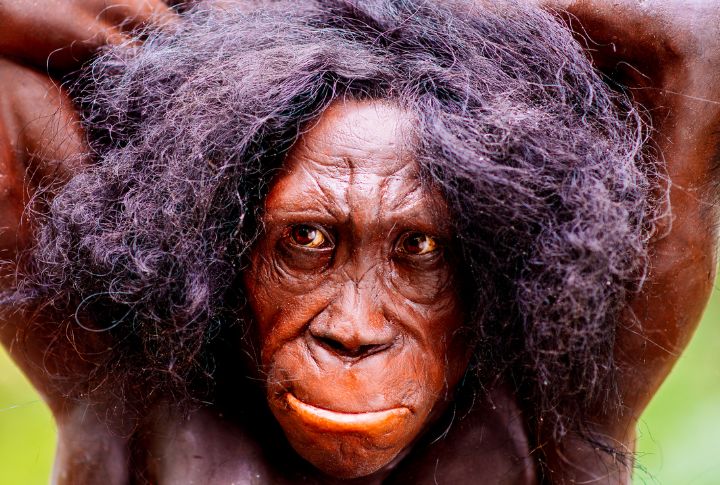

This is the story of Ardi (Ardipithecus ramidus), one of our special ancestors called hominis. The discovery of her 4.4-million-year-old skeleton challenged everything we knew about evolution. Let’s go through the remarkable details that made Ardi a turning point in our origins, and you’ll never see early humans the same way again.

Discovered In Ethiopia (1994)

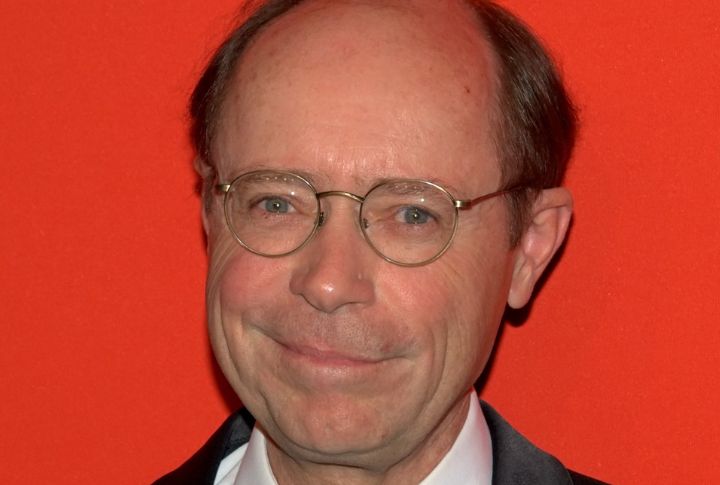

Ardi’s skeletal remains were unearthed in 1994 by paleoanthropologist Tim D. White and his international team in the Afar region of Ethiopia. It took over a decade to carefully excavate and analyze her crushed bones. She became one of the most painstakingly reconstructed hominin fossils ever studied.

Pelvis Mixed Ape And Human Traits

Ardi’s pelvis revealed a striking mix of shapes: broad and short like a human’s, yet with muscles like a chimpanzee suited for climbing. Under evolutionary biologist Owen Lovejoy’s guidance, researchers found how our early ancestors evolved.

Didn’t Walk On Her Knuckles

Forget the chimp-like shuffle, Ardi’s hands told a different story. She didn’t rely on knuckle-walking. Her fingers were flexible, made for gripping branches. That freedom hinted at better abilities for balance, and even early object manipulation long before tools appeared.

Stood Upright Like Us

Her restructured skeleton offered researchers one of the earliest, clearest glimpses into how our lineage first adapted to two feet. Ardi’s lower spine curved forward, which kept her upright. That’s an ability apes never developed, but humans still share.

A Toe That Could Grasp Trees

The distinct foot structure of Ardi is yet another example of adaptation. With an opposable big toe, she could grasp trees and branches with ease. It was an important tool for safety when foraging or escaping predators in the trees.

Small Teeth, Peaceful Behavior

A closer look at Ardi’s teeth revealed something remarkable: her canines were small and equal in size between males and females. The absence of fighting fangs suggested reduced aggression and more cooperation, which are behavioral shifts that laid the groundwork for future human social connections.

Brain Stayed Ape-Sized

Though only about 300–350 cubic centimeters (roughly one-fifth the size of a human brain), the ancient hominin’s brain matched a chimp’s in scale. Still, scientists think it supported simple social awareness and coordination. This tells us that cognitive evolution may have begun well before brains grew larger in later species.

Lived In Woodlands

Surrounded by trees instead of open grasslands, our early ancestor made her home in dense Ethiopian woodlands. Fossils and animal remains confirmed the setting. This discovery challenged the long-held “savanna theory” and revealed that upright walking first started in forest habitats rather than in wide, open plains.

Ate Fruits And Small Animals

Ardi wasn’t a picky eater. Dental studies show her meals included fruits, leaves, and the occasional small animal or even an insect. The omnivorous menu offered the flexibility needed to survive in forests and helped her species thrive through shifting climates.

Didn’t Use Tools

No stone tools were discovered with her remains, which means using tools was a later development in hominins, specifically Australopithecus and Homo. Ardi’s hand lacked the adaptations needed for precise manipulations, which is a necessity for tool-making.