Samurai swords. Ritual suicides. Stoic warriors standing under cherry blossoms. Sound familiar? Pop culture has served us a buffet of samurai stereotypes—some delicious, others questionable at best. But the truth? It’s a lot messier and way more interesting. Let’s slice through the fiction first with five fantasies that miss the target, then sharpen our focus on the realities that earned their legendary edge.

Every Samurai Wielded A Katana

When most people picture a samurai, they imagine a katana first. Conversely, on the battlefield, it was often the spear that reigned, especially during the Sengoku era. Earlier still, longbows led the charge. Katanas gained fame later, mostly for status, and even civilians wore them.

All Samurai Strictly Followed Bushido

The image of a samurai bound by unshakable honor makes for great stories. In reality, bushido—meaning “the way of the warrior”—was never a fixed code. Samurai conduct changed by clan or circumstance. The term emerged much later, shaped by Confucian scholars in a peaceful, post-war society.

Samurai Were Noble Defenders Of The Weak

It’s tempting to imagine samurai as protectors of the people; however, villagers often feared them. They collected taxes harshly and cracked down on uprisings with force. Loyalty flowed upward, not toward commoners. That righteous image we associate with them today emerged through propaganda, not firsthand experience.

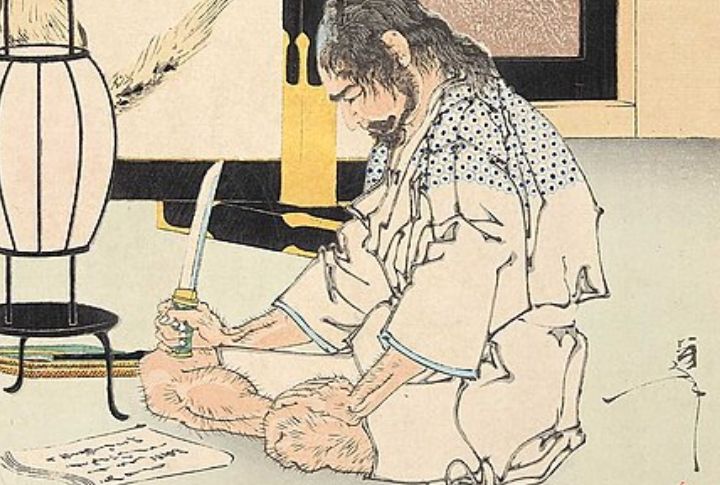

Seppuku Was Common And Always Heroic

Today, seppuku sounds like a bold personal choice, despite history painting a different picture. This ritual act of self-disembowelment aimed to restore honor but was typically ordered as punishment. A second stood ready to assist. Over time, stories romanticized the practice, even if many samurai feared and avoided it.

Only Men Served As Samurai

Women didn’t simply stay behind closed doors. Many led troops and defended fortresses in battle. Tomoe Gozen stands out as a well-known example. Although their battlefield roles faded after peace returned, gravestones still confirm their presence to offer lasting proof that their stories were grounded in truth.

Now that the myths are cleared away, let’s explore the five truths that reveal who the samurai really were—and how their influence lingers even today.

Samurai Were A Privileged Military Elite

A large number of samurai held real authority by managing villages as local officials. During the Tokugawa shogunate, their elite status was formalized to maintain control. They could legally wear two swords, a symbol of class. Paid in rice (koku), their income depended on the farmers.

Samurai Trained In Many Weapons Beyond The Sword

Firearms arrived in Japan during the 1500s, and warlord Oda Nobunaga used them with precision. Archery remained sacred, especially in ceremonies. Manuals like Heiho Okugi Sho, or “Secret Essentials of Martial Arts,” stressed adaptability. Samurai also trained in mounted archery, called yabusame, and used spears in organized group formations.

Samurai Loyalty Was Real, Though Code Varied By Era

Uesugi Kenshin, a famed warlord, inspired loyalty that exceeded simple obedience. Loyalty to daimyo, or feudal lords, was typically personal, although not always consistent. The 47 Ronin, masterless samurai called ronin, are a well-known case. As warfare gave way to administration, loyalty shifted, yet many remained committed during chaos.

Women In Samurai Families Took Active Roles

Women received formal training in weapons and strategy, preparing them for real responsibilities. Nakano Takeko, for example, defended castles with bravery. While husbands fought, the majority of women managed estates. Their diaries show involvement in politics and alliances. Even instructional texts from the Edo period recognized women as stewards of honor rather than silent figures.

The Samurai Class Shaped Modern Japan

Even today, Japanese fashion and corporate ideals borrow samurai aesthetics. In the early 1900s, bushido was reshaped for Imperial use. Martial arts like kendo and judo grew from battlefield techniques. Though abolished by Meiji reforms, most samurai transitioned into government and education, only to leave behind a cultural legacy still felt.