What appears to be destruction isn’t always a result of anger. Hatshepsut’s shattered statues were treated in ways that can be confusing and sometimes misleading. But careful research has shown the reasons weren’t simple—and they weren’t all the same. Through ten archaeological discoveries, this read walks you through the destruction of the statues.

Ritual Deactivation, Not Revenge

In ancient Egypt, statues were believed to hold spiritual energy, so dismantling them at the joints served to neutralize that power. Importantly, it wasn’t personal, and it wasn’t unique to her. Male pharaohs received similar treatment, indicating that this was a standard ritual practice rather than a gendered backlash.

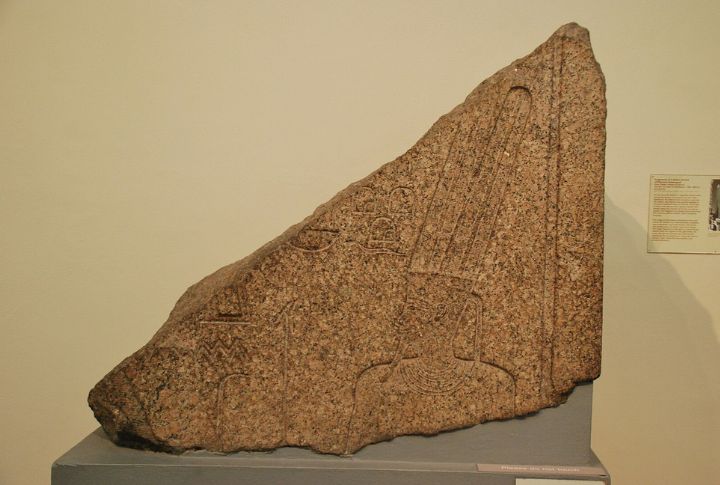

Reuse As Building Material

A broken pharaoh statue could make great patio material. Over time, chunks of Hatshepsut’s monuments ended up in terraces and other later constructions. This suggests a practical approach rather than symbolic erasure. The reuse spanned multiple periods, which complicates any assumption that the disfigurement came from a single episode of destruction.

Political Pressure From Elites

Power always comes with strings. In Hatshepsut’s case, Thutmose III may have acted not out of spite but under pressure from elites unsettled by her reign. Her leadership disrupted royal succession norms, which likely prompted a cleanup effort to restore dynastic order. Within that context, the statue damage appears strategic—not vengeful.

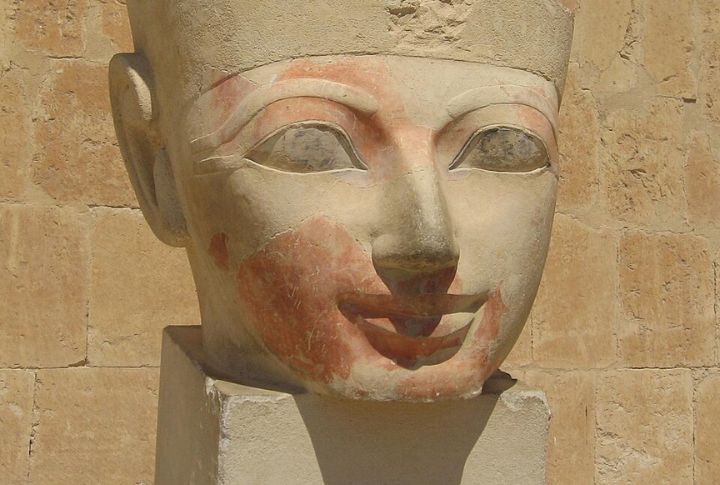

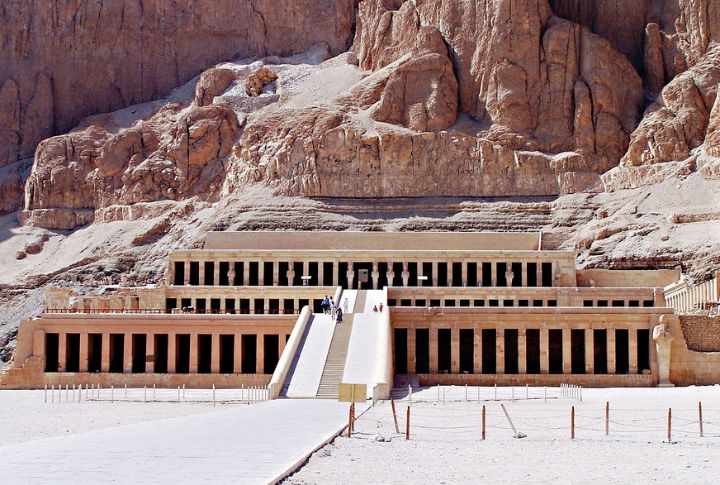

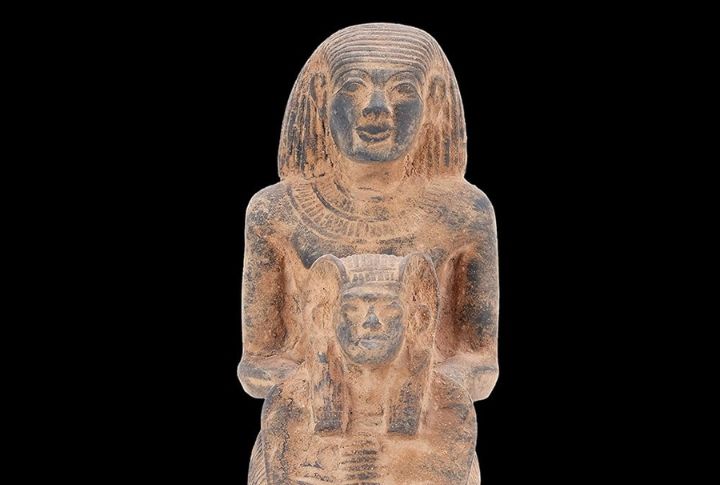

Evidence From Deir El-Bahri Excavations

At Deir el-Bahri, some statue fragments were buried methodically, while others were carefully placed or stored instead of smashed. These patterns suggest the demolition wasn’t chaotic. Notably, excavations revealed that Hatshepsut’s statues were handled with intention. Together, these details align with the site layout, which points to organized disposal tied to ceremonial behavior.

Karnak Cachette Comparison

Nothing about Hatshepsut’s statue treatment was unique. At Karnak, statues of several rulers—hers included—were broken and buried in strikingly similar ways. The breakage followed known deactivation patterns, consistent across different reigns. Even officials connected to her, such as Senenmut, were treated the same; this suggests a broader ritual custom.

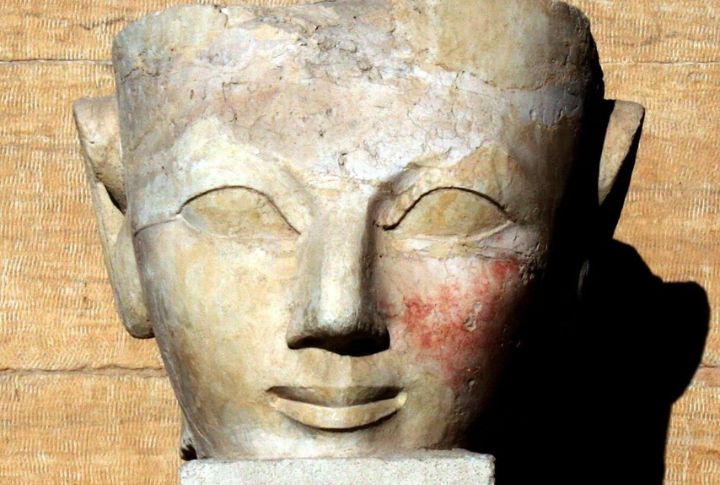

Modern Reinterpretation And Gender Bias

Early on, people believed the defacement of her statues aimed to erase a woman in power. But that theory doesn’t hold up. Scholars now recognize Hatshepsut’s masculine imagery as part of royal tradition. Her statues weren’t targeted because she was female—they were misunderstood through a modern lens that’s now being corrected.

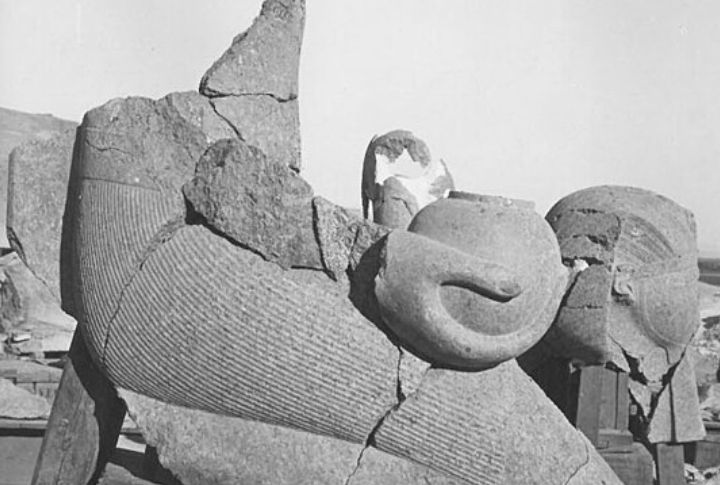

Logistical Constraints Of Statue Removal

Too heavy to move and too big to ignore, many of Hatshepsut’s statues were dismantled right where they stood. To deal with the bulk, workers dismantled them on-site and kept only the usable pieces. The rest was left behind, and quarry zones exhibit rough shaping and clear discard marks, indicating a decision shaped by convenience.

Ideological Shifts In Later Periods

Hatshepsut’s legacy didn’t vanish—it was repurposed. Some later rulers reused her monuments to shape their image, while others removed or altered specific statues. These choices reflected shifting political and religious priorities. That kind of selective editing suggests her memory wasn’t erased, but adapted to suit the narrative each successor needed.

Natural Damage Vs. Intentional Destruction

Not all the wear on Hatshepsut’s statues came from human hands. Over time, erosion and long periods underground took their toll. In certain instances, heads and limbs were damaged during reburial or subsequent excavation. In the end, something that may seem like political erasure could be the result of nature’s slow, steady process.

Multi-Phase Damage Timeline

It’s easy to assume all the deterioration happened under Thutmose III, but the timeline tells a different story. Some statues were ritually broken, while others were reused in construction, and many suffered from gradual erosion caused by aging and prolonged exposure to natural conditions. This range of degradation spans centuries, not a single moment in Hatshepsut’s reign.