It’s tempting to picture Rome as too big to fail: armies conquering continents, emperors presiding over vast cities. But Rome didn’t collapse in a single moment. It got hollowed out from within, worn down by disaster after disaster until only the shell remained. Here’s the full story.

Corruption Choked The Empire

In 193 CE, the Praetorian Guard auctioned the imperial throne to the highest bidder—Didius Julianus—openly selling power in the heart of Rome. Later, emperors rewarded loyalty with titles, not merit. Bribes became prerequisites for office. By the 4th century, trust in government had collapsed. Citizens no longer expected justice—only favors and survival.

A Carousel Of Emperors

The Crisis of the Third Century (235–284 CE) saw 26 emperors rise and fall in just 50 years. Many, like Gordian II and Gallienus, were killed by rivals or their own troops. Civil wars erupted across provinces. Breakaway states like the Gallic Empire and Palmyrene Empire splintered Rome while plagues ravaged its core.

The Empire Was Too Vast To Hold Together

Stretching across Europe, Asia, and Africa, Rome’s communication and transport networks were marvels of the ancient world. But distance bred disunity. Provincial governors acted more like independent rulers, and distant crises grew too large, too fast for Rome to control.

Economic Collapse Ran Deeper Than Taxes

Rome’s economy cracked under the pressure of endless military spending. Inflation spiraled, the middle class disintegrated, and local economies grew fragile. As landowners left with their wealth, cities crumbled, and citizens lost the infrastructure that once sustained their lives.

A Split That Couldn’t Be Repaired

In 285, Emperor Diocletian split the empire into East and West to manage it better. The East flourished; the West faltered. As centuries passed, their differences hardened, and when the West called for help, the East increasingly looked the other way.

Enemies Were Already Inside

As Rome expanded, Germanic tribes like the Goths settled inside its borders—first as refugees, then as threats. Mass migrations in the late 300s overwhelmed Roman defenses, creating pockets of instability deep within what was supposed to be secure territory.

Religion And Politics Collided

By the late 300s, Church and State were inseparable. Bishop Ambrose of Milan defied Emperor Theodosius I, forcing him to do public penance for the Massacre of Thessalonica in 390. Popes like Leo I negotiated with Germanic warlords as imperial authority crumbled. Bishops gained judicial and administrative roles once reserved for governors.

The Huns Upended The Balance

When the Huns stormed into Europe in 370 CE, they sent terrified refugees flooding into Roman territory. Rome, already brittle, struggled to accommodate the displaced peoples. Over the centuries, the chain reaction of migrations and invasions that followed helped push the empire past the point of no return.

The Gothic Revolt Was A Death Blow

In 378, Gothic refugees, mistreated by Roman officials, rose up. At the Battle of Adrianople, they annihilated a Roman army and killed Emperor Valens. It was a turning point that shattered Rome’s military prestige, particularly in the vulnerable Balkans.

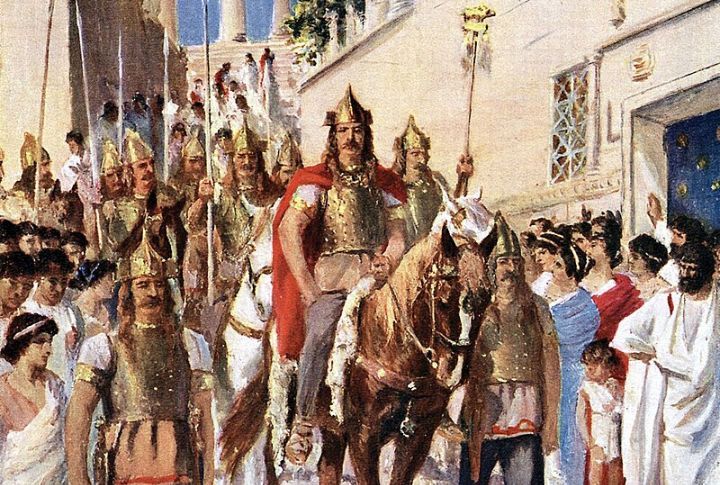

The Myth Of Invincibility Shattered

The sack of Rome in 410 by King Alaric’s Visigoths sent shockwaves across the empire. Although Ravenna had become the political capital, Rome’s symbolic heart had been pierced. Its fall exposed the crumbling reality behind the empire’s once-mighty image.

Situation Of The Forgotten West

During the 400s, the Western Empire was unraveling fast. Mediolanum, once a capital, lost that status in 402. Rome was sacked in 410 and again in 455. As wicked kings like Odoacer and later Theodoric ruled Italy, Western provinces, like Gaul, Hispania, and Britain, were abandoned to chaos or carved up by new kingdoms.

Barbarians Became Rome’s Generals

In the 5th century, military power shifted into the hands of foreign-born commanders. Men like Stilicho, a Vandal, and Ricimer, a Suebi-Goth, held real power behind the throne. They manipulated puppet emperors and prioritized tribal loyalties. Rome’s armies were still fighting—but no longer for Rome alone.

The Army Lost Its Roman Core

The traditional Roman enlistment collapsed as the empire increasingly relied on foederati—Germanic allies like the Franks, Visigoths, and Huns—to fight imperial battles. After the death of Stilicho in 408 CE, even key garrisons were handed to non-Roman commanders. The legions still marched, but their loyalty lay elsewhere.

Military Strength Without Civic Backbone

In the 5th century, Roman forces in Gaul and Hispania were stretched thin, even as barbarian kingdoms advanced. Roads and supply chains fell apart, especially after the Vandals’ takeover of North Africa in 439, which cut grain routes to Italy. Starved of resources, legions defending the Rhine and Danube frontiers withered.

After The Vandals, The Empire Crumbled

In 455, the Vandals delivered another brutal blow, looting Rome with terrifying efficiency. Barely two decades later, in 476, a Germanic general named Odoacer unseated the last Western emperor. By then, imperial authority was a hollow echo of its former self.

Trade Routes Fell Apart

When the Vandals captured Carthage in 439, they seized control of Rome’s grain supply from North Africa. Piracy surged across the Mediterranean, and key ports like Ostia declined. Disrupted trade crippled urban markets, inflated prices, and left once-thriving cities dependent on unreliable local sources for survival.

The Laws No Longer Protected The People

Rome’s legal system once defined citizenship and order. But by the 4th and 5th centuries, it served only the elite. Tax burdens crushed the poor while aristocrats found loopholes or bought their way out. Justice became arbitrary. As confidence in the law vanished, so did loyalty to the state.

Citizens Withdrew From Public Life

As cities grew unsafe and taxes soared, elite Romans abandoned civic duties and retreated to private villas. Estates in the countryside became self-sufficient, bypassing local government. At the start of the 5th century, even senatorial families withdrew from urban life. This completely eroded the communal backbone that had once supported Roman identity.

No One Rebuilt What Fell

After disasters, like the sack of Rome in 410 or repeated frontier losses, little effort was made to rebuild. Temples, libraries, and forums decayed. With civic pride gone and tax bases gutted, even basic repairs ceased. Decay became the default, not the exception. It ultimately accelerated the empire’s visible collapse.

Rome Knew It Was Dying

During the mid-5th century, Roman historians already started to describe the empire’s fall. Sidonius Apollinaris wrote of senators ignoring the state. Salvian of Marseille blamed Roman greed and injustice for divine punishment. Even emperors like Majorian admitted the system was beyond repair. So, Rome didn’t fall suddenly but unraveled with full awareness.