Some jobs make perfect sense—teacher, builder, doctor. Others? Not so much. History is full of professions that were once taken seriously but now sound completely absurd. These 20 jobs weren’t hobbies or pranks but legitimate ways to earn a living. Most have faded into obscurity, leaving stories of how people survived.

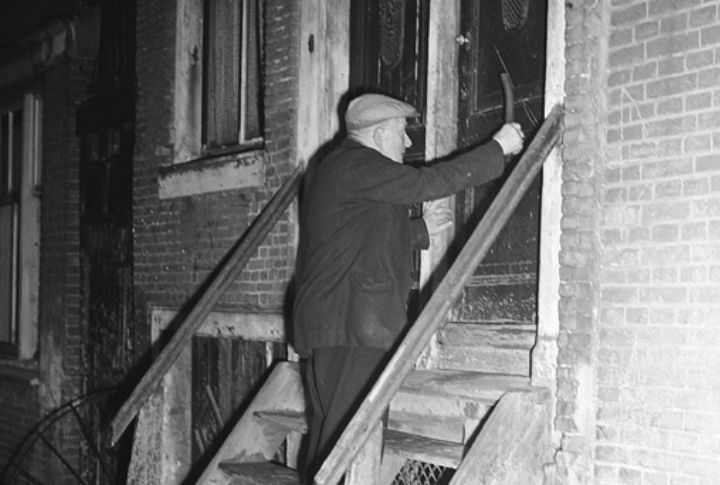

Knocker-Uppers (19th Century)

Before sunrise in coal towns, knocker-uppers patrolled streets with long sticks, tapping second-story windows to wake factory workers. Some used pea-shooters for extra reach. They weren’t paid much—sometimes merely a few pence a week—but in communities where alarm clocks were rare, they were more reliable than roosters and far less annoying.

Town Criers (Medieval Era)

Long before newspapers, town criers dressed in eye-catching livery and read official news aloud in public squares. Their bell-ringing wasn’t just for show. It signaled people to gather and listen. Since they voiced royal decrees, harming one could land you in serious trouble. In a way, they were walking headlines with legal authority.

Plague Doctors (17th Century)

Europe’s cities were desperate during the plague years, and many so-called doctors were barely trained. Still, they walked the streets in beaked masks stuffed with herbs, believing the scent blocked “bad air.” Some wrote detailed death records; others ran. The outfit was more theater than science, but it became oddly iconic.

Leech Collectors (19th Century)

Wading into muddy ponds barefoot and bleeding wasn’t glamorous, but it was common for rural women who gathered medicinal leeches. The leeches fed directly on the collectors, who risked infections and anemia for pennies. Doctors bought them by the jar, convinced bloodletting could treat everything from headaches to hysteria.

Herb Strewers (1660s–1830s)

Royal halls reeked of chamber pots and sweat. That’s where herb strewers came in, scattering lavender, chamomile, and mint across the floors of Buckingham Palace. Their job blended sanitation with symbolism, as certain herbs were believed to ward off illness. Herb strewers disappeared with the arrival of indoor plumbing and fewer royal noses.

Breaker Boys (Late 1800s)

Children as young as eight were put to work sorting coal from stone in deafening breaker rooms. They sat hunched for hours, bare hands black with coal dust, often losing fingers or worse. It was dangerous, yet accepted. Reformers fought for decades to end this brutal chapter of child labor.

Lamplighters (19th Century)

Evenings once belonged to the lamplighter. Armed with a long pole and steady feet, they’d light gas lamps by hand, often climbing precarious ladders. The best routes were memorized, like choreography. For a time, it was considered respectable work, with uniforms and pride—until electricity made their artistry obsolete almost overnight.

Rat Catchers (Victorian Era)

London’s rat problem was more than a nuisance. It was a full-blown health crisis. Enter the rat catcher, armed with traps, poison, and often a terrier. Jack Black, Queen Victoria’s own catcher, even bred fancy-colored rats as pets. Between bites, boils, and fleas, it wasn’t a safe job, but it paid in rodents.

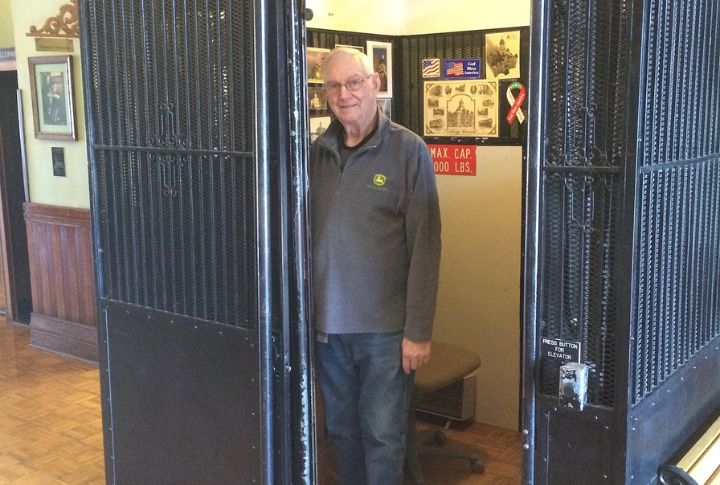

Elevator Operators (Early 1900s)

Operating a manual elevator wasn’t as simple as pressing a button. It took timing, muscle memory, and charm. Department stores hired women trained to announce floors with poise and precision. In posh hotels, their uniforms were crisp, their small talk rehearsed. Automation eventually took over, but not without a fight from loyal regulars.

Milkmen (Mid-20th Century)

They wore white uniforms, drove boxy trucks, and knew every porch on the route. Milkmen delivered fresh bottles daily, long before pasteurization or reliable refrigeration. Glass clinked, cream rose to the top, and neighbors traded gossip at the door. It was a part of the morning rhythm.

Lectors (19th Century)

In cigar factories, work was loud, repetitive, and long. So, workers pooled wages to hire lectors—educated readers who sat on high platforms and read aloud newspapers, novels, and political treatises. It wasn’t background noise. It was culture. Some workers even learned literacy this way. Radios killed the lector but not the spirit.

Human Computers (Early–Mid 20th Century)

Without any calculator or computer, women in lab coats used to calculate trajectories, fuel loads, and engineering specs by hand. These “computers” filled entire rooms with charts and scratch paper. Their math launched rockets and mapped war zones. Their names weren’t remembered until stories like “Hidden Figures” finally made them visible.

Crossing Sweepers (1800s)

Picture cobblestone streets slick with horse manure, spilled ale, and worse. Crossing sweepers—often children—cleared paths through the muck so the wealthy could pass unsoiled. Some wore uniforms; others just hoped for a coin. It was barely a job, barely dignified, but it kept many stomachs slightly less empty.

Groom Of The Stool (Tudor Period)

Don’t let the title fool you. The Groom of the Stool aided the king in relieving himself, yes—but he also held extraordinary access to the monarch’s private thoughts. Trusted with intimate moments, grooms sometimes rose to political power. In a palace full of plotting courtiers, bathroom proximity meant influence, not mockery.

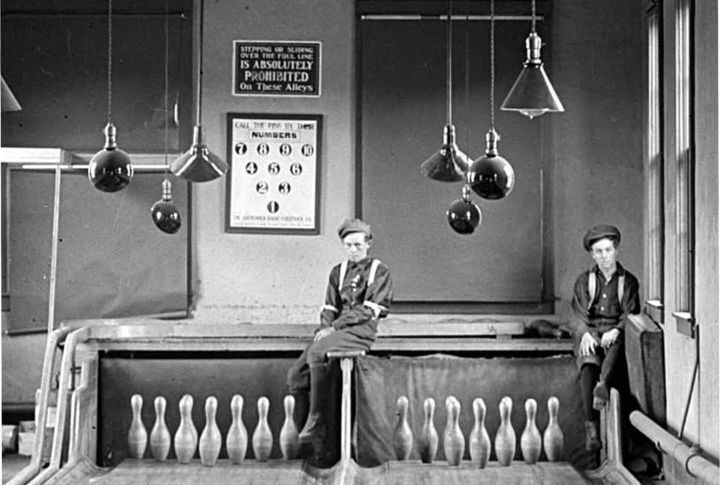

Pinsetters (Early 20th Century)

Before automatic machines, young boys were stationed behind bowling alleys, resetting pins by hand between every roll. The job was fast, noisy, and full of bruised shins. They worked for tips and the occasional soda, dodging balls for fun—or survival. Eventually, automation knocked them out like a perfect strike.

Mudlarks (18th–19th Century)

Life along the Thames wasn’t picturesque for mudlarks. They waded into raw sewage and sharp debris, scavenging nails, rope, or coal to sell for pennies. Most were children. It was dangerous, filthy work, but sometimes it meant dinner. In a way, they were the river’s earliest recyclers—just without gloves or glory.

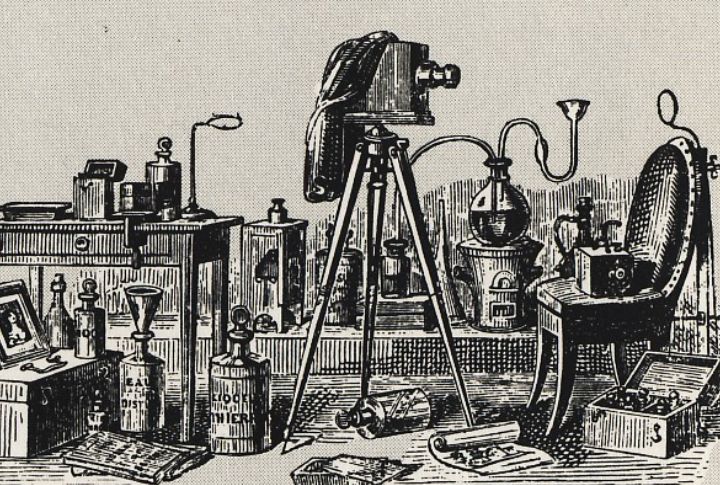

Daguerreotypists (Mid-19th Century)

Long before selfies, daguerreotypists labored over silver-plated copper sheets to capture single, ghostly portraits. Exposure could take 30 minutes, and subjects had to sit perfectly still, often with head braces. The process was chemistry, patience, and artistry all rolled into one. Their studios were toxic but oddly glamorous.

Ice Cutters (Pre-1900s)

Before refrigerators, winter was the harvest season for ice. Workers used saws and horse-drawn plows to extract frozen slabs from lakes, hauling them into insulated icehouses. Timing mattered: cut too early, and it melted; too late, and the lake thawed. The work was often fatal. But without them, food spoiled fast.

Resurrectionists Or Body Snatchers (18th–19th Century)

To obtain cadavers, anatomy students and professors turned to a shadowy class of suppliers: resurrectionists. These grave robbers crept into cemeteries under the cover of night, digging up freshly buried bodies to sell to doctors for dissection. Some even had regular contracts with medical schools. Their work was illegal and morally murky.

Powder Monkeys (18th–19th Century, Naval Era)

Aboard warships, the cannon crews needed a steady supply of gunpowder, and that job fell to the smallest and fastest boys on deck, called powder monkeys. Typically, between 8 and 14 years old, the kids carried sacks of powder under intense fire. One wrong move could blow them and everyone around sky-high. Their bravery was legendary.