American art has given us some of the most breathtaking, thought-provoking, and downright unforgettable paintings in history. Some make you feel like you’re stepping into another world, while others stop you in your tracks. This lineup will have you looking at art in a whole new way.

George Washington (Lansdowne Portrait) By Gilbert Stuart (1796)

Commissioned as a diplomatic gift, this painting shows Washington in full presidential grandeur, arm outstretched like he’s delivering a historic speech. The idea behind this was to show Britain that America was thriving under Washington’s leadership. Stuart, a master portraitist, painted multiple versions, including the one on the one-dollar bill.

Declaration Of Independence By John Trumbull (1818)

In this ultimate Fourth of July snapshot, John Trumbull meticulously depicted Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and others presenting the draft to Congress, though a fun fact: this scene never actually happened this way. The painting is more symbolic than literal, but that didn’t stop it from becoming iconic.

Madame X By John Singer Sargent (1883–1884)

The striking portrait of Madame Virginie Gautreau, a Parisian socialite, was meant to be about her beauty and elegance, but it instead sent Paris into an uproar. Originally, one strap of her gown was slipping off her shoulder, which was considered too risque, forcing Sargent to repaint it.

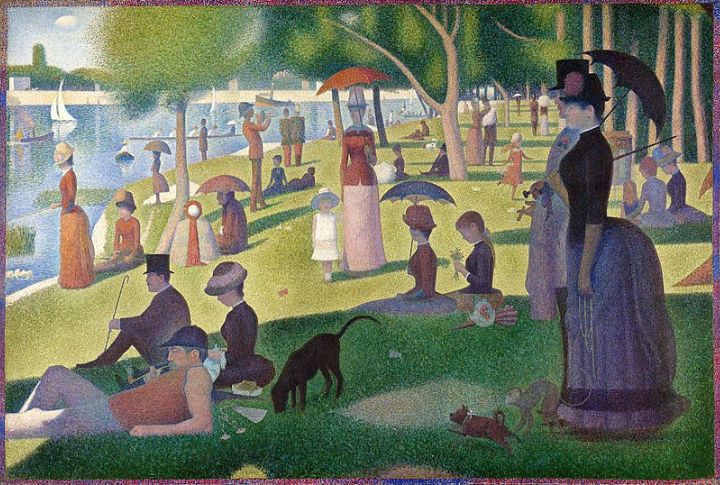

A Sunday Afternoon On The Island Of La Grande Jatte By Georges Seurat (1884-1886)

If patience were a painting, it would be “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” It’s a scientific masterpiece made up of millions of tiny dots of color. Seurat spent two years placing each dot, proving that art and math go hand in hand.

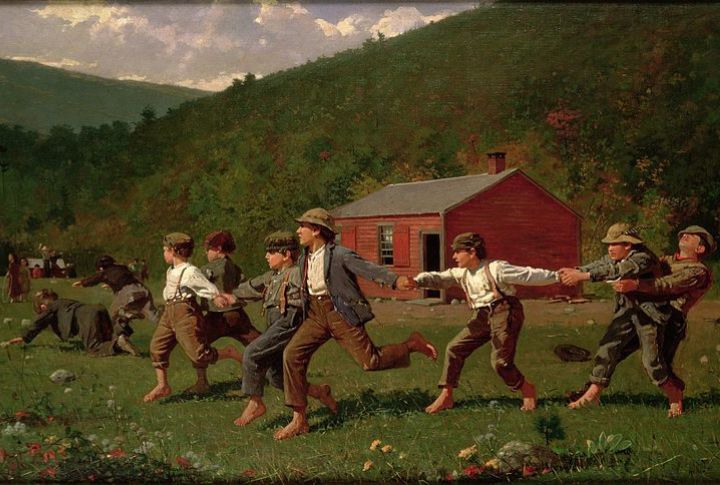

Snap The Whip By Winslow Homer (1872)

“Snap the Whip” by Winslow Homer is pure childhood nostalgia on canvas. The group of schoolboys holding hands, running at full speed, and trying not to fall is a fitting metaphor for America’s resilience after the Civil War. Though life was industrializing, this painting celebrates the innocence of youth.

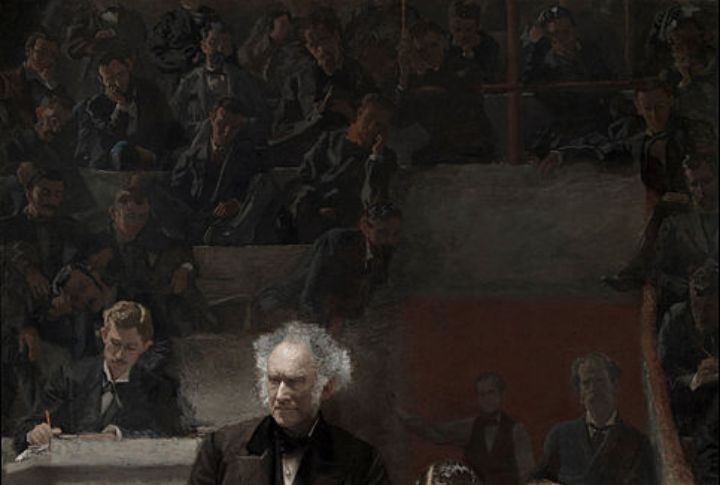

The Gross Clinic By Thomas Eakins (1875)

Instead of royalty or high society, Eakins painted Dr. Samuel Gross mid-lecture, performing surgery in a 19th-century operating theater. Eakins, who was into realism, wanted to show medicine as it truly was: gritty, intense, and groundbreaking. Though initially controversial for its graphic detail, it is now considered a masterpiece.

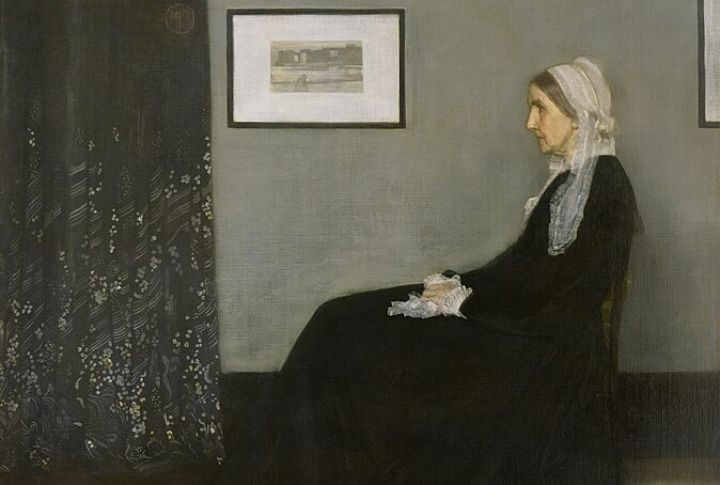

Whistler’s Mother By James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1871)

Sometimes, a simple portrait speaks volumes. “Whistler’s Mother” is one of the most famous paintings of maternal dignity, often called the American Mona Lisa, despite being painted in London. The image of Whistler’s seated mother, dressed in black, is like the 19th-century version of “Mom’s not mad, just disappointed.”

Daughters Of Edward Darley Boit By John Singer Sargent (1882)

Most family portraits are about warmth and connection, but “Daughters of Edward Darley Boit” is more mystery than memory. Sargent, known for his ability to capture personality with subtlety, turned what could have been a simple family portrait into a study of growing up and the quiet space between sisters.

The Child’s Bath By Mary Cassatt (1893)

There’s something intimate about “The Child’s Bath,” like a quiet, everyday moment between a mother and child. Cassatt used bold outlines and flattened perspective to give the scene a delicate yet modern feel. Unlike many male artists of her time, she depicted the quiet strength of women without idealizing them.

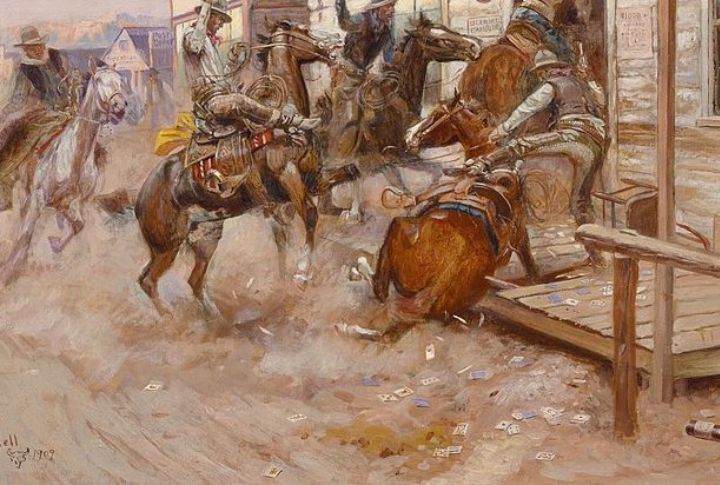

In Without Knocking By Charles M. Russell (1909)

With galloping horses, flying hats, and an unsuspecting crowd in all directions, the painting practically moves. Russell, one of the greatest artists of the American West, had a knack for storytelling, and he painted the West just as he had experienced it: raw, rugged, and full of adventure.

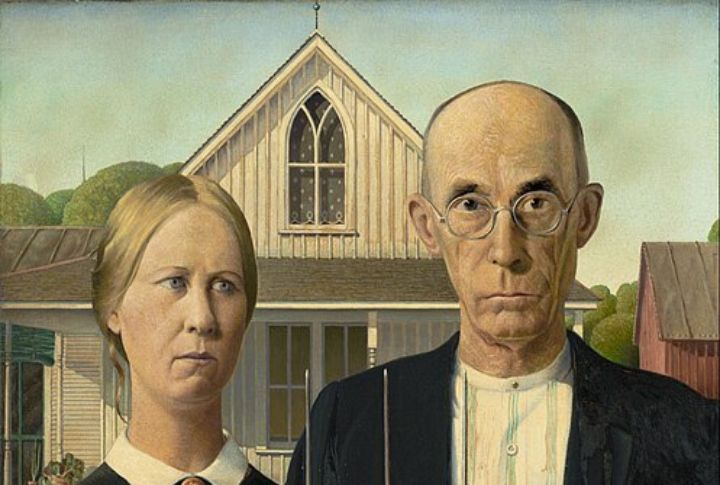

American Gothic By Grant Wood (1930)

“American Gothic” is one of the most recognizable paintings in American art. Wood wanted to capture the resilience of rural America during the Great Depression. Some saw it as a tribute to hard-working Americans, while others thought it was satire. Either way, it became an instant classic!

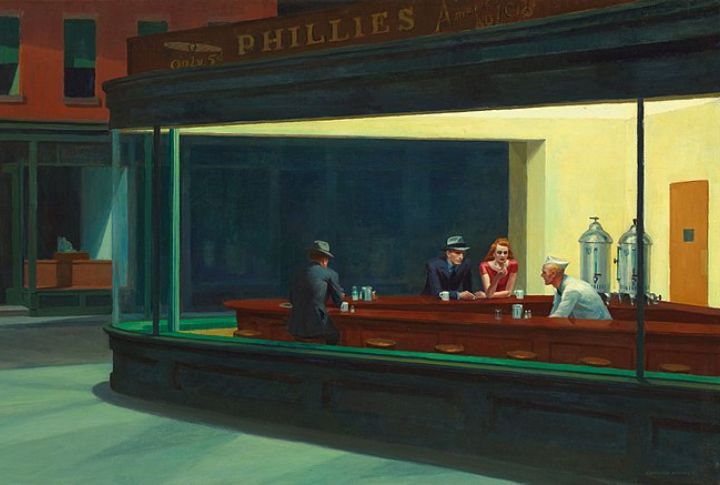

Nighthawks By Edward Hopper (1942)

If loneliness in the big city is a painting, it would be “Nighthawks.” The warm, artificial light spills onto the sidewalk, contrasting with the cold, empty darkness outside. Hopper never gave a clear explanation of the painting’s meaning, but the feeling of isolation resonated deeply, especially during wartime America.

Freedom From Want By Norman Rockwell (1943)

The ultimate Thanksgiving scene, “Freedom From Want,” is part of Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” series. This one focused on an idealized American holiday filled with warmth, togetherness, and plenty of mashed potatoes. He painted it during World War II as a symbol of abundance and security.

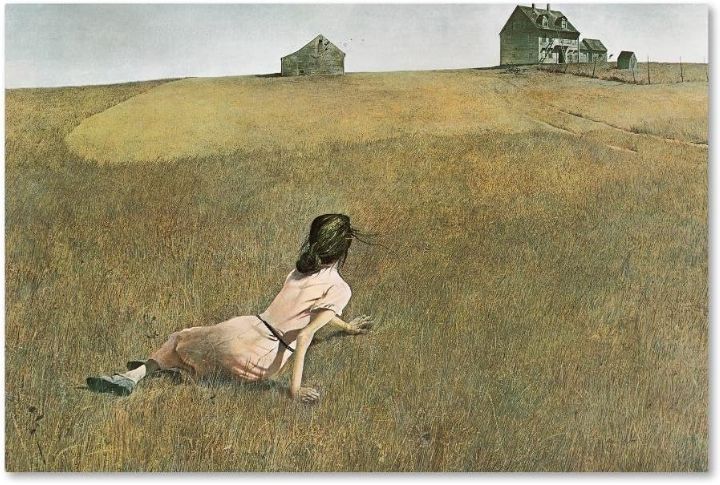

Christina’s World By Andrew Wyeth (1948)

At first glance, it seems like a peaceful country scene, but then you notice something unusual: the woman isn’t standing or walking—she’s crawling toward the farmhouse in the distance. The subject, Christina Olson, was Wyeth’s neighbor in Maine, who had limited mobility and was an icon of resilience and determination.

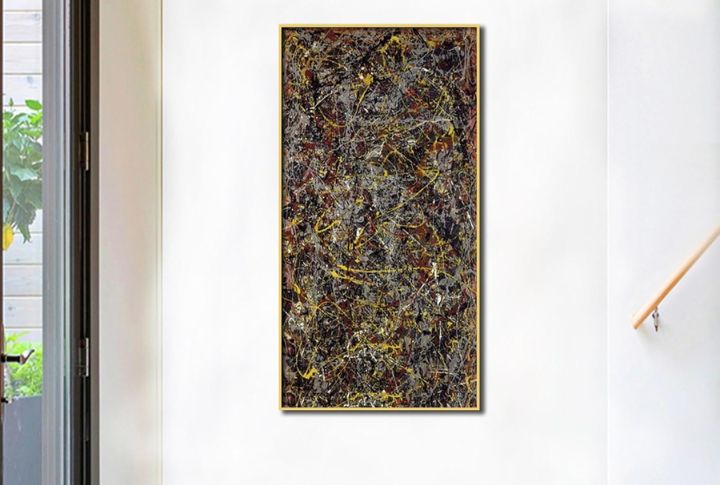

No. 5, 1948 By Jackson Pollock (1948)

This massive 8-foot-long masterpiece is a tangled web of yellow, brown, and gray splatters, created using Pollock’s signature “drip technique.” Instead of using a brush, he let the paint fall from above, moving around the canvas like a performer. He believed art should capture raw emotion, not just recognizable images.

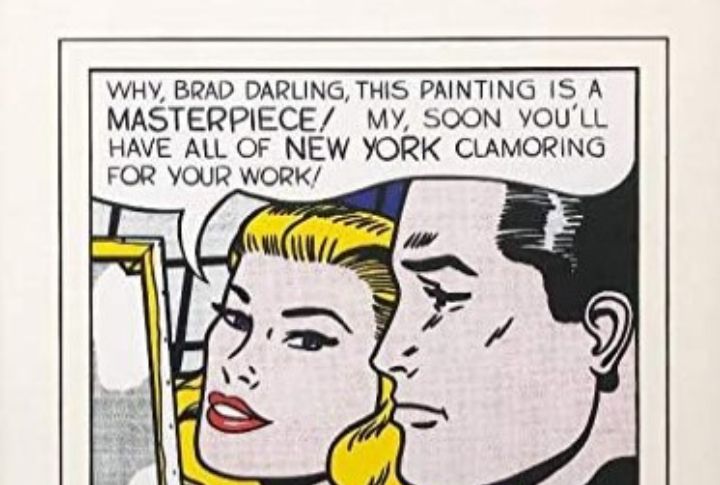

Masterpiece By Roy Lichtenstein (1962)

A playful prediction, “Masterpiece” became part of Lichtenstein’s rise to stardom. At the time, Pop Art was challenging the seriousness of traditional fine art, and he was one of its most controversial pioneers. By the end of the decade, his name was everywhere, just as the fictional Brad predicted.

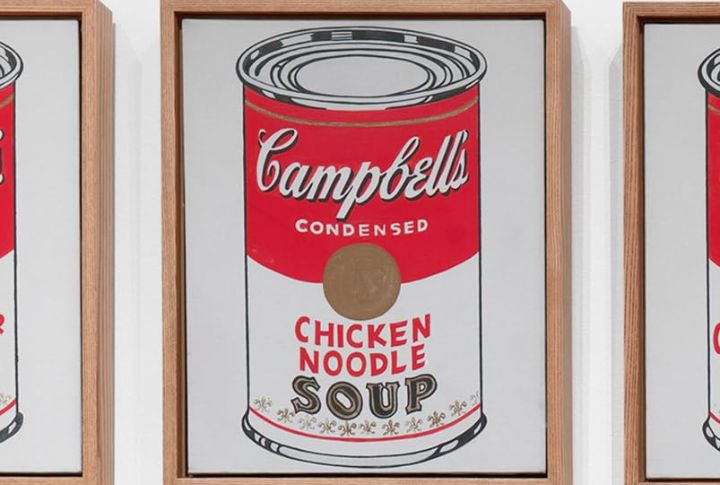

Campbell’s Soup Cans By Andy Warhol (1962)

Before 1962, soup was just soup, but then Andy Warhol turned Campbell’s soup cans into one of the most famous artworks of all time. This series of 32 nearly identical canvases, each featuring a different flavor, was about consumerism, branding, and mass production in modern America.

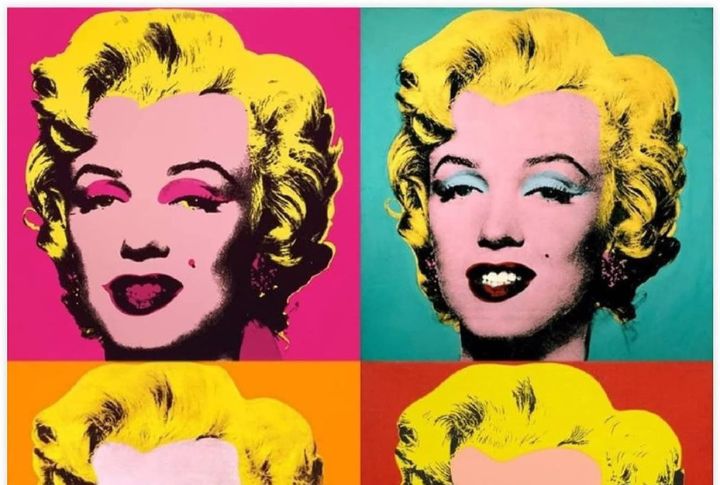

Marilyn Diptych By Andy Warhol (1962)

Created shortly after Marilyn Monroe’s death, this massive artwork features 50 images of Marilyn, split into two contrasting panels, a peek at fame, beauty, and mortality. The diptych format, reminiscent of religious altarpieces, turns Marilyn into a modern icon, but the gradual fading suggests the fleeting nature of stardom.

The Dinner Party By Judy Chicago (1974–1979)

“The Dinner Party” is a feminist installation that redefines what art can be. This triangular banquet table features 39 place settings, each honoring a significant woman. From Cleopatra to Virginia Woolf, every set includes a personalized plate, many with fierce, sculptural designs inspired by the female body.

The Oxbow by Thomas Cole, 1836

Thomas Cole painted “The Oxbow” as a visual contrast between untouched wilderness and cultivated land, capturing America at a crossroads. The left side is stormy and wild, while the right is peaceful and orderly. Plus, hidden in the brush is a tiny self-portrait of Cole himself, quietly observing the scene.